The failed petition of Christopher McPherson, Richmond, Virginia, 1810

In 1810, Christopher McPherson submitted a petition to the Virginia General Assembly, the State’s legislative body. In this petition, he asked to be exempted from a newly enacted ordinance which prohibited people of African descent from riding in a carriage in the city of Richmond, Virginia’s capital.1 This was a time when the free Black population of Virginia, and in the US South as a whole, was experiencing growing pressure for being Black in a society that justified slavery by skin colour. Slavery came to be abolished in the northern states, yet in the South, it intensified and spread. When the legislative framework around free people of colour grew tighter, they saw many of their political and civil rights curtailed. On an economic level, domestic White competitors, European immigrants and some employers made efforts to exclude them from the more respectable and independent jobs.2 The prohibition on using a carriage severely limited the professional and private mobility of many people of colour, and McPherson decided to resist.

This petition is just one among several documents which collectively form an ‘archival bundle’, including newspaper advertisements, certificates vouching for McPherson’s character, his manumission document and various letters. It also contains his A Short History of the Life of Christopher McPherson, an autobiographic narrative which McPherson attached to the various documents supporting his case.3 Even more than his petition, the autobiography is a remarkable source which communicates the voice of a free Black man in a virtually undistorted way and affords valuable insights into his inner world.

Christopher McPherson’s files are archived in the Library of Virginia but Encyclopedia Virginia, the American Antiquarian Society and other institutions have made the rich sources, alongside reconstructive information, available online. This allows every student and interested reader to learn about McPherson and the world he lived in.4 Drawing on this material, I will discuss in depth the petition and McPherson’s struggle in the context of his time and place. To better understand his individual experience, I will draw on the additional material found in the archival bundle and conclude with some reflections on the opportunities, limits and coerciveness of the documentary record. Archives, after all, are not only ‘places’ or ‘institutions’, as Caio Simões de Araújo and Srila Roy have emphasised. They work ‘as an underlying metaphor and a call for thorough contextualization and a radical re-imagination of the historical experiences’.5

The trigger

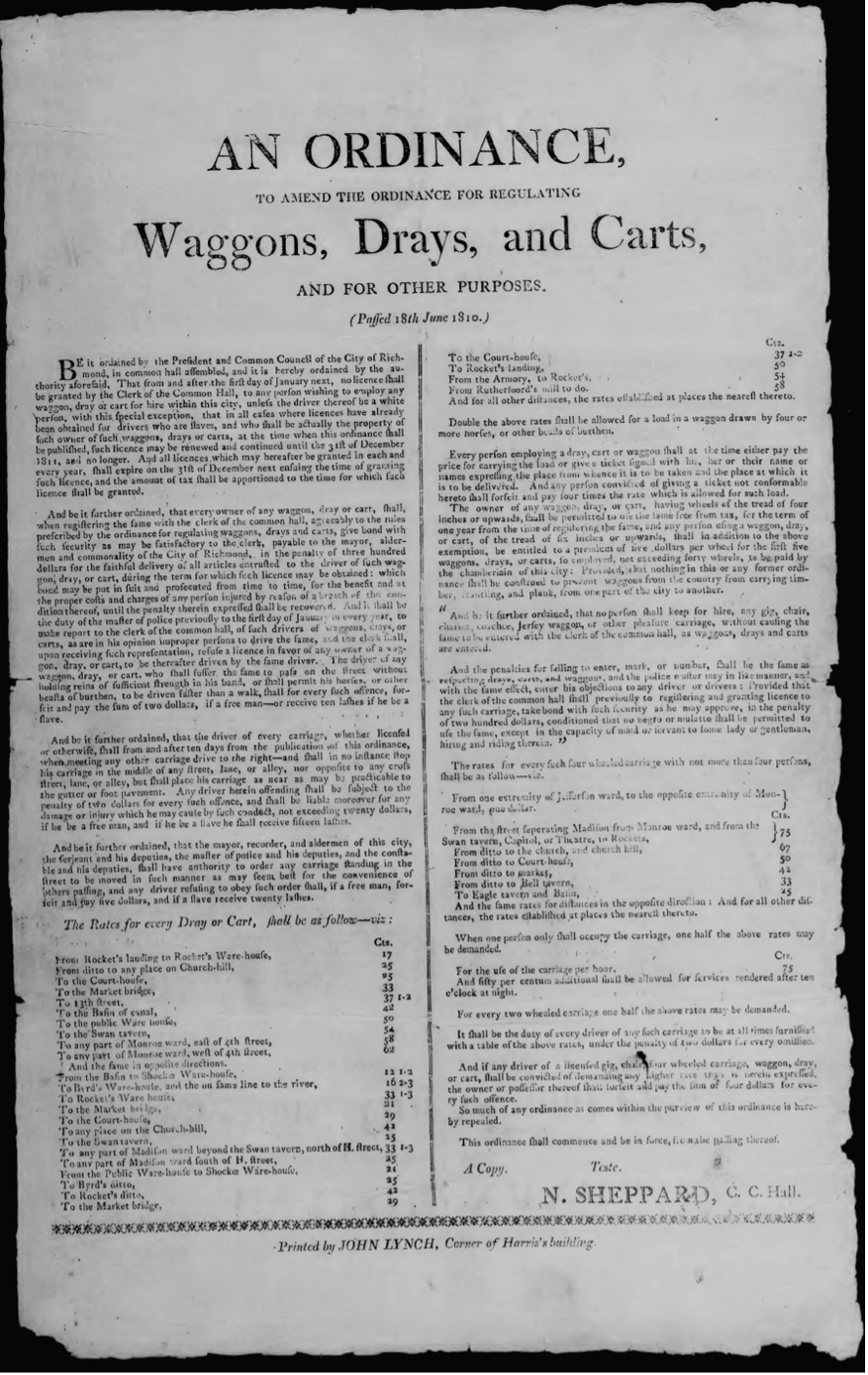

On 18 June, 1810, the Virginia General Assembly passed a new law entitled ‘AN ORDINANCE, TO AMEND THE ORDINANCE FOR REGULATING WAGGONS, DRAYS AND CARTS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES’ ordaining ‘That from and after the first day of January next, no license shall be granted by the Clerk of the Common Hall, to any person wishing to employ any waggon, dray or cart for hire within the city, unless the driver thereof be a white person.’ The ordinance further provided ‘that no person shall keep for hire, any gig, chair, … or other pleasure carriage, without causing the same to be entered with the clerk of the common hall.’ Licensing, ‘in the penalty of two hundred dollars’, would be provided under the condition ‘that no negro or mulatto shall be permitted to use the same, except in the capacity of maid or servant to some lady or gentleman, hiring and riding therein.’6

Requiring registration and licences was a common strategy of city authorities to collect information, divide the heterogeneous population and earn some money. As in McPherson’s case, it could be about mobility and the precondition to work in a particular sector, or it could be about the right to buy firearms, own dogs or sell liquor. Almost always Black people did not get these licences, and McPherson took up the pen to become an exception.

The antebellum South had a troubled relationship with its free Black population. American society defined freedom through slavery and justified slavery with race which made free people with Black skin a visible contradiction to Southern notions of race and freedom. At the start of the nineteenth century, there already existed a modest, self-preserving free Black population in the young United States. It had emerged from antislavery sentiments during and after the American Revolution, a time that had enabled enslaved men and women to press for their freedom. With the rise of cotton, American planters saw new moneymaking opportunities in the global economy, and slaveholders began to curtail manumissions. Yet, they could not reverse the growth of the free population of colour. Around 1810, this population had increased enough to ensure and expand its future autonomous growth. White Southerners came to see free Black people as a threat, both to the particular institution of slavery and the wider social order.7

The petition

Free men and women of colour in Virginia were not allowed to vote. They could not sit on a jury, run for office or travel without fear of being molested. What they could do was write petitions. Frequently used by people of all backgrounds, however humble, petitions were, very generally, ‘demands for a favour, or for the redressing of an injustice, directed to some established authority’. They are an important window into studying ‘ordinary people as historical actors’ by shedding light on those realities not documented elsewhere. Authorities often granted petitions to cement their legitimate rule, a global practice which reaches back thousands of years.8 In America, the right ‘to assemble and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances’ was included in the US Bill of Rights in 1791.9

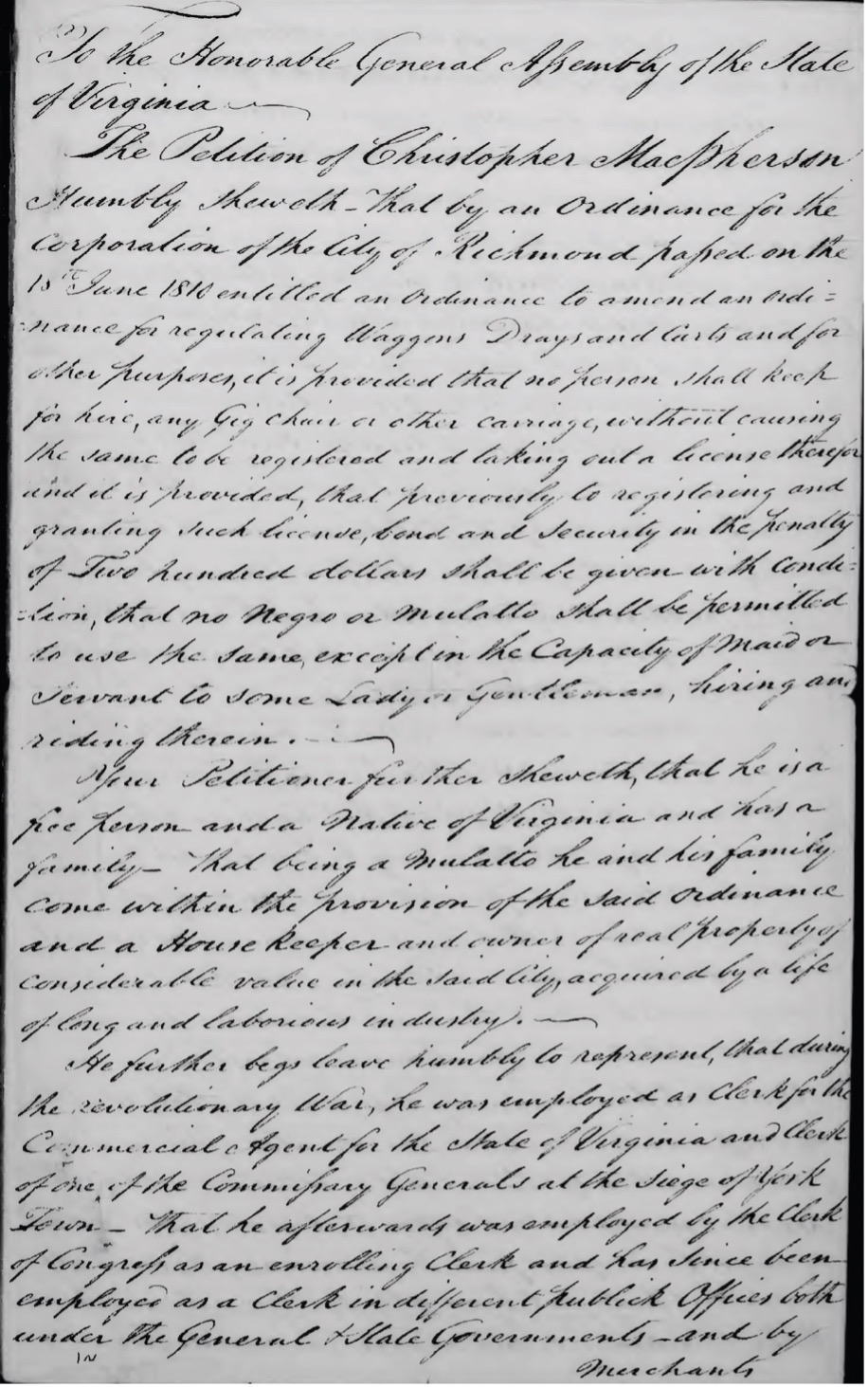

A petition includes the addressee, the request, the motivation and a degree of specific information about the petitioner. Thanks to his education as a clerk, McPherson was literate while countless of his contemporaries needed a professional writer to meet the formal requirements of a petition.10 To be sure, McPherson adhered closely to the required language and met all the other criteria too which made him believe that he could win this battle for his mobility and business. His petition opens: ‘To the Honorable General Assembly of the State of Virginia. The petition of Christopher McPherson humbly sheweth’, after which he repeated relevant excerpts of the 1810 ordinance letter by letter. Then, his own account followed:

Your petitioner further sheweth, that he is a free person and a Native of Virginia and has a family. That being a Mulatto he and his family come within the provision of the said ordinance and a House Keeper and owner of real property of considerable value in the said city, acquired by a life of long and laborious industry.11

Giving us a great deal to consider in this one sentence, McPherson first stressed his free status and nativity, thereby linking his very presence in Virginia to a claim of ‘unassailable belonging, one grounded in birthright citizenship’.12 His mention of having a family hoped to build the impression that he was an honourable man committed to providing for his dependents, a value cherished in antebellum Southern masculine culture.13 McPherson also informed the General Assembly that the new ordinance affected him and his family because they were of African descent, and at the same time did not fail to mention in passing that he was a ‘mulatto’. This remark of (self-)identification implied that he was lighter-skinned than the majority of free people of colour in the Upper South, which typically went hand-in-hand with a higher social standing than that of darker-skinned people.

With a switch to reporting his contribution to the economic system, McPherson referenced his property ownership of a house and other real estate ‘of considerable value’, again highlighting his local attachments. Associating himself with the propertied classes of society reflected his strategy to signal his belonging to the higher circles of Richmond. His ‘life of long and laborious industry’ added the finishing touches to his personification of the ‘self-made man’ and other capitalist qualities so readily endorsed by nineteenth-century elites.14 McPherson’s message to the legislature was clear: He might be a man of colour but he was also one of them.

Likely sharing much more information than comparable petitions, McPherson added:

He further begs leave humbly to represent, that during the Revolutionary War, he was employed as Clerk for the Commercial Agent for the State of Virginia and Clerk of one of the Commissary Generals at the siege of York Town. That he afterwards was employed by the Clerk of Congress as an enrolling Clerk and has since been employed as a Clerk in different publick Offices both under the General & State Governments—and by merchants & others in examining & settling accounts and other business of that nature, which requires fidelity industry and a knowledge of accounts. … Your Petitioner trusts he may say, without fear of contradiction, that he has given general satisfaction to his employers and that he has uniformly sustained and deserved the character of an honest and industrious man.15

By listing his past employments and appearing confident about the affectionate judgements of his previous employers, McPherson tried to transmit his general knowledge of ‘how the system worked’. Nonetheless, his petition was also a testament to his large network, alluding to different government levels and private business circles. This professional-related part of his petition bridged the way to the most personal sentence, in which McPherson accounts:

That your petitioner and his wife being both advanced in life and occasionally subject to disease—it has happened and may again happen, that the occasional use of a carriage when they are unable to walk, may be necessary not only for their comfort but their health and for the carrying on the business of your petitioner, which lays in various parts of the said City.16

Since health conditions, unlike unusual economic success, affected many people of advanced age, it is doubtful whether this argument weighed particularly strongly in the General Assembly’s assessment. Conversely, McPherson’s concerns about the expected negative impact of the ordinance on his economic life went right to the heart of its intention. After all, limiting the social and economic mobility of people of colour was exactly what the new law intended. Surprisingly, the Committee for Courts of Justice of the General Assembly did not reject McPherson’s appeal outright. Instead, they forwarded the petition with a favourable report to the House of Delegates. There, however, the petition was not followed up and Christopher McPherson’s efforts failed.17

The petitioner

His rise

Christopher McPherson was the son of an enslaved woman, Clarinda, and a Scotsman named Charles McPherson in Louisa County, Virginia. Since the legal status of children in slaveholding America followed the status of the mother, McPherson was born a slave. The date of his birth must have been between the years 1760 and 1765. Several authors seem to read between the lines that the relationship with his father included a degree of care, and this was when the course of his life began to diverge from that of so many other enslaved Americans. According to testimonies, Charles McPherson managed to have a friend, David Ross, buy his infant son from his mother’s owners. McPherson later wrote that he ‘was brought up and emancipated by David Ross’. In Fluvanna County, Ross provided a solid education, sending Christopher to school, employing him as a storekeeper and training him as a clerk.18

Following his earlier years in rural Louisa and Fluvanna counties, McPherson’s subsequent biography became manifestly urban. This was no coincidence. Manumitted slaves and free Black Americans were disproportionally drawn to urban centres so that in the Upper South one-third of free people of colour came to live in the cities and towns.19 By 1810, the year that Christopher McPherson wrote his petition, Richmond counted 9,700 inhabitants, of which 3,700 were enslaved. He himself was one of the 1,200 free Black Richmonders.20

His career included several stages of clerking in different offices and companies, both government- and privately run, including the High Office of Chancery.21 He also worked as a clerk for the US House of Representatives, published frequently in local newspapers and had met Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.22 In 1792, Ross made McPherson’s manumission official, stressing that he had lived as a free man for several years. Ross, meanwhile residing in the city of Richmond, certified that:

as a reward for the fidelity and integrity of Christopher McPherson, well known to me from his earliest years to this date; altho[ugh] doomed to slavery under the laws of this State, I have long since Emancipated him, and this day give it all the forms required by law. … I do by these presents Emancipate and set free the said Christopher, and I, for myself my heirs executors and administrators, do, relinquish all my right, title Interest and Claim whatsoever as a slave to the said Christopher, either to his person or to any estate he may acquire, without any interruption, from me or any other person, or persons Claiming by form or under me, hereby acknowledging the said Christopher McPherson to be henceforth entitled to all the privileges of a free born person.23

By then, McPherson was about 29 years old, and was officially free, preparing for a life with ‘all the privileges of a free-born person’.

Things were looking good for him. Over the years, he managed to build up a successful mercantile business, transporting goods about the city and even shipping tobacco to Europe.24 He adopted a truly capitalist lifestyle, renting more expensive houses every couple of years, purchasing real estate in and around the city and renting it out or selling it on with a profit.25 His work as clerk was independent and respectable, conforming to nineteenth-century aspirations of working for none other than oneself. Owning and driving in carriages was a prerequisite of his business.

With the new ordinance of 1810, however, things took an unexpected turn. Without any warning that he saw coming, McPherson suddenly realised, ‘it deprives him of rights to which he is entitled under the laws and Constitution of this Commonwealth’.26 His belief in existing—official and customary—law gave him a false sense of security, and so McPherson evoked legislation and formal justice to convince the legislators of his cause:

Your petitioner is and always has been disposed to conform to all such laws and rules as the publick good might be thought to require by those placed in authority, nor would he now complain, did he not sustain real inconvenience from the said ordinance and were he not apprehensive, that as he and his wife grow older and more infirm, this inconvenience will be greatly heightened. Wherefore your petitioner humbly prays, that your Honorable Body will be pleased to take his case into Consideration and that he may be protected in the enjoyment of such rights as are given him by the General Laws of this Commonwealth and that your Honorable Body will be pleased to enact such regulations as will prevent those rights from being infringed.27

McPherson underestimated the volatile attitudes of White Southerners towards free Black people and the hardening colour line of the early nineteenth century. ‘[A]ll the privileges of a free-born person’, as David Ross had put it—and McPherson relied on—did not extend to free-born persons of African descent. The 1810 law ‘brought reality crashing in’.28

… and fall

The year 1810 indeed marked the beginning of the fall of Christopher McPherson. From that point on, everything seemed to go wrong. He could not secure a bank loan although his repeated requests were backed up by esteemed White citizens. After opening a night school for Black men’s education, he received public defamation and had to defend himself against allegations of ‘maintaining a nuisance’. A fight with his wife at home, possibly related to the limitations that the ordinance placed on his transport business, resulted in charges of ‘disturbing the peace’. McPherson then spent three weeks in jail.29

Archivist and historian Edmund Berkeley Jr. attributed the failure of McPherson’s petition at least partially to the fact that McPherson could not resist to include fantasies of the imminent end of the world in it.30 Since the late eighteenth century, McPherson had acted on long-held beliefs ‘that these United States were the new Zion’ and he was its ‘messenger to the world’.31 His Christian fanatism certainly contributed to his later referral to the ‘lunatic asylum’ in Williamsburg, when he told the court, after being arrested for acting strangely in the streets, that he was ‘Pherson, son of Christ, King of Kings, and Lord of Lords, and prevailed them to read the 19th chapter of the Revalations, which contains my appointment’.32

Although he was found sane by the board of directors and released, he was unable to get back on track with his business. McPherson continued to be consumed by the ‘divine revelation’. He toured various Virginia cities, circulating handbills with his prophecy in Norfolk, Portsmouth, Manchester and Petersburg before returning to Richmond. Due to his absence in jail and the mental hospital, he suffered severe financial loss and parts of his property were sold at auction.33

Despite or rather due to his beliefs, McPherson appears to have been a man with remarkable self-confidence. Still hopeful about the legal justice system, which had let him down consistently, he went on to sue several people for exorbitant sums, including, but not limited to, the master of police for $50,000 and each member of the court who had found him insane, $100,000.34 It seems that McPherson did not accept and perhaps not understand, the limitations White supremacist America placed on him as a man of colour.

My quest

While McPherson’s petition and narrative are highly intriguing and extremely relevant to understanding antebellum Virginia, I was interested in runaway slaves—men and women who had escaped slavery and went to the cities and towns of the slaveholding South.35 Their strategy was to remain undetected by the authorities, which is why it is difficult to find direct information about them. Largely without detailed sources produced by and about them, I needed proxies to find out about their experiences. Since fugitive slaves in Richmond either pretended to be self-hired slaves—who were sent out by their owners to work on their own—or tried to pass as free people of colour, I looked for persons representative of the broader free Black population. This is how I stumbled upon the petition of Christopher McPherson; yet as just laid out, it soon turned out that he was a rather special case.

At first glance, McPherson’s biography often reads as if he channelled his energies towards making it in the ‘White world’. He proudly emphasised that as a master clerk, he had several Whites working under him; in 1802, he testified as a witness in a case at the District Court and stated that his testimony was considered above those of two White men.36 Very unusually, he also acted as executor of the will of James Ross, his former master’s brother.37 When living in Richmond, McPherson contributed to paying for street reparations, a voluntary civic duty of the wealthy and a generous gesture of the elite. With all his knowledge and strategic decisions, McPherson must have known that he could never be his White supporters’ friend or equal. After all, they would never need his vouching in return but they did share some interests, viewpoints and a level of material comfort.

Yet perhaps this is a route where the biases of the archive mislead us. The night school for men of colour that McPherson opened in 1811 is an unmistakable example of his commitment to and belief in the Black community. Encouraged by high enrolment numbers, he even placed an advertisement in the local paper, animating others throughout the country ‘to establish similar institutions’ to expand ‘light and knowledge among this class of people…’38 Strikingly, he included enslaved men in his programme, yet women are notably absent from the plans for his school as well as in his autobiography, except for the occasional mention of his wife Mary ‘Polly’ Burgess McPherson.39 For his Black school, McPherson chose a White tutor, yet many Whites resented aspirations of interracial learning. Shortly after the advertisement was published, the editor of the newspaper, although seemingly—and surprisingly—in favour of Black education, folded to the pressure of White Richmonders and decided to take it down. As Berkeley aptly put it, ‘the educational ideas of the editor and Christopher McPherson were too revolutionary by one hundred fifty years’.40

It is safe to say that McPherson was a unique case of an enslaved man who beat the odds, only to find himself subject to the grim reality of antebellum America a few years later. He is a prime example of the worsening legal, political and social conditions of free people of colour which marked the entire course of the antebellum period up to the Civil War and the end of American slavery.41

His example, however, is instructive in other ways too, as his biography begs to be linked to the questions: Who even were these people who left traces in the archives? Whose voices can we recover today? Whose can we not, or only by searching for new ways of reading the sources? Petitions are compelling because, in theory, they are regarded as a democratic tool, even before the advent of modern Western democracy.42 Historians often stress the inclusiveness of legislative petitions, especially in the colonial Americas, where even enslaved people resorted to this measure.43 But McPherson’s case invites us to ask who was able to write petitions in the first place. Assuming that people reckoned with at least a slight success rate, it is highly telling that even McPherson’s petition, which evidenced so many promising arguments and was backed up by numerous White benefactors, was rejected. If someone like McPherson failed, what kind of signal did this give to other people of colour with life courses which were less pleasing to White society? It is our job, then, to find creative ways to make inferences about why ‘all these other people’ did not write petitions and what this can tell us about their lives.

The coerciveness of the archives

Several historians have written eye-opening studies around the questions of what is in the archives, how it is archived and who decides on these matters.44 With power asymmetries revolving around gender, ethnicity and (colonial) oppression looming large, the coercion in the archives is constructed similarly to coercion in other spheres, such as the world of work. Indeed, for labour historians, they are mutually constitutive. To understand and reconstruct the historical experiences of marginalised people, we need to ‘study modalities of domination and dependence’,45 both in the historical context and in the documentary record.

While all of this is also valid here, there is more to say about petitions and McPherson’s particular struggle. Although petitioning is often understood as an opportunity, for McPherson, it emerged as a last resort. He stated,

that he has represented his case to a Number of the members of the corporation of the city of Richmond by letter, requesting that his case might be laid before the Common Hall and that he might be excepted from the provisions of the said Ordinance but hath not been able to obtain a decision thereon.46

Having previously tried to use his local networks, the petition to the State legislature evidenced the lack of alternatives which McPherson faced. Besides the sheer fact of seeing himself compelled to write it, he also had to disclose sensitive data. He might have been proud to share some information, such as his impressive career development, but he also felt under pressure to reveal personal information, including his and his wife’s health conditions. Much less obviously, he was forced to present himself as the subservient, obedient Black man who ‘knew his place’ in a White supremacist society. He had to squeeze his fight—the fight for the life he knew—into a standardised text and standardised language, a preconditional requirement of a legislative petition. Archives, thus, hold many things that contain different levels of coercion.

We should also discuss the question of whether McPherson passed on the coercion which he experienced. Far from acting willingly or even consciously, he testified in his petition that he agreed with the new ordinance. He wrote that he agreed that free Black Richmonders should not possess or ride in carriages but since he was old and needed it for his business—and, by extension, because he was wealthy—that he should be allowed:

Your petitioner submits without a murmur, to those Laws of the Commonwealth, which impose disabilities on that class of people to which he belongs and as he is not disposed to deny, that there may be persons with respect to whom, the ordinance aforesaid might properly apply, but he humbly concieves [sic] that the said ordinance is unjust as it respects himself and family.47

Notably, while this rhetoric of deference was an inherent feature of petitioning, McPherson supported, rather than undermined, the status quo of power relations.48 He very explicitly confirmed the validity of the racist law but sought an individual exemption. What he wanted was to influence legislation and to create a loophole. Theoretically, this loophole could be used by others like him. In reality, however, there were very few like him. Without being able to measure the effects of this kind of strategic consideration on other people of colour, McPherson did contribute to an imagination of the Black population which was divided by economic rank, skin colour and personal relations with Whites.

This is not to suggest that McPherson’s petition was linked to any malevolent intentions nor should we attach it with a weight it likely did not possess. Yet we should still approach it with the utmost mindfulness. By echoing and reproducing discrimination, depreciative attitudes and psychological violence, the archives can contribute to perpetuating racism, classism, sexism and other -isms which inform and are informed by coercion. This occurs on many different levels, more or less visibly, interrelated and interwoven. All the work of social historians to ‘read the archives against the grain’ is necessary precisely because ‘assertions of geopolitical, racial, and religious supremacy’ are cemented in the documentary records and ‘have served to render historically invisible many activities of subjugated peoples.’49

However, taking up Marisa Fuentes’s words, McPherson’s petition and narrative can also be read as his attempt to leave traces which counteract the ‘manner in which the violent systems and structures of White supremacy produced devastating images’ of people of African descent. These images continue to ‘pervade the archive and govern what can be known about them’.50 With this perspective, Christopher McPherson’s petition has the potential to emerge not only as an act of individual but of broader antiracist and anticolonial resistance.

Bibliography

An Ordinance, to Amend the Ordinance for Regulating Waggons, Drays and Carts, and for Other Purposes. 18 June 1810. In Petition of Christopher MacPherson to General Assembly. 10 December 1810. Legislative Petitions. Library of Virginia.

Berkeley, Edmund Jr. “Prophet without Honor: Christopher McPherson, Free Person of Color”. Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 77:2 (1969): 180–190.

Bill of Rights (1791). Article the Third. National Archives (20 September 2022). URL: https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/bill-of-rights. Accessed 25 September 2023.

Blumenthal, Sidney. A Self-Made Man: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, 1809–1849. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014.

Carter, Rodney G.S. “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence”. Archivaria 61 (2006): 215–233.

De Vito, Christian G., Juliane Schiel, and Matthias van Rossum. “From Bondage to Precariousness? New Perspectives on Labor and Social History”. Journal of Social History 54:2 (2020): 644–662.

Deed of Emancipation. David Ross to MacPherson. 2 June 1792. Henrico County. In Petition of Christopher MacPherson to General Assembly. 10 December 1810. Legislative Petitions. Library of Virginia.

Fuentes, Marisa J. Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Johnson, Jessica Marie. “Markup Bodies: Black [Life] Studies and Slavery [Death] Studies at the Digital Crossroads”. Social Text 36:4 (2018): 57–79.

Jones, Martha. Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Levi, Amalia S. “Archives of Empires, Archives of Race: A Reflection on the 2023 Archives, Slavery & Race-Making Summer School”. dependency.blog (2 October 2023). URL: https://dependency.blog/archives-of-empires-archives-of-race-a-reflection-on-the-2023-archives-slavery-race-making-summer-school. Accessed 2 October 2023.

McPherson, Christopher. A Short History of the Life of Christopher McPherson, Alias Pherson, Son of Christ, King of Kings and Lord of Lords: Containing a Collection of Certificates, Letters, &c. Written by Himself. Lynchburg, VA: Printed at The Virginian Job Office, 1855.

Müller, Viola Franziska. Escape to the City: Fugitive Slaves in the Antebellum Urban South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022.

Paul, Heike. The Myths that Made America: An Introduction to American Studies. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2016.

Petition of Christopher MacPherson to General Assembly. 10 December 1810. Legislative Petitions. Library of Virginia.

Population of Virginia—1810. URL: http://www.virginiaplaces.org/population/pop1810numbers.html. Accessed 8 January 2019.

Premo, Bianca. The Enlightenment on Trial: Ordinary Litigants and Colonialism in the Spanish Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Simões de Araújo, Caio, and Srila Roy. “Introduction: Intimate Archives: Interventions on Gender, Sexuality and Intimacies”. African Studies 81:3-4 (2022): 255–265.

Slaton, Amy E., and Tiago Saraiva. “Editorial”. History and Technology (14 November 2023). DOI: 10.1080/07341512.2023.2275357. Accessed 21 November 2023.

van Voss, Lex Heerma. “Introduction: Petitions in Social History”. International Review of Social History 46 (2001): 1–10.

Van Vranken, Sadie. “Christopher McPherson”. Black Self-Publishing. URL: https://www.americanantiquarian.org/blackpublishing/christopher-mcpherson. Accessed 17 November 2023.

Wolfe, Brendan. “Christopher McPherson (ca. 1763–1817)”. Encyclopedia Virginia (7 December 2020). URL: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/mcpherson-christopher-ca-1763-1817/#start_entry. Accessed 25 September 2023.

Wood, Nicholas P. “A ‘Class of Citizens’: The Earliest Black Petitioners to Congress and Their Quaker Allies”. William and Mary Quarterly 74:1 (2017): 109–144.

Würgler, Andreas. “Voices from among the ‘Silent Masses’: Humble Petitions and Social Conflicts in Early Modern Central Europe”. International Review of Social History 46 (2001): 11–34.

Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Zaret, David. “Petitions and the ‘Invention’ of Public Opinion in the English Revolution”. American Journal of Sociology 101:6 (1996): 1497–1555.

Footnotes

Petition of Christopher MacPherson to General Assembly, 10 December 1810, Legislative Petitions, Petition 5633, Library of Virginia. Please note that McPherson also appears as “MacPherson” in the archive.↩︎

Viola Franziska Müller, Escape to the City: Fugitive Slaves in the Antebellum Urban South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022), 133–135.↩︎

Christopher McPherson, A Short History of the Life of Christopher McPherson, Alias Pherson, Son of Christ, King of Kings and Lord of Lords: Containing a Collection of Certificates, Letters, &c. Written by Himself (Lynchburg, VA: Printed at The Virginian Job Office, 1855).↩︎

Sadie Van Vranken, “Christopher McPherson”, Black Self-Publishing, URL: https://www.americanantiquarian.org/blackpublishing/christopher-mcpherson, accessed 17 November 2023. For his memoirs and associated documents, see Brendan Wolfe, “Christopher McPherson (ca. 1763–1817)”, Encyclopedia Virginia (7 December 2020), URL: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/mcpherson-christopher-ca-1763-1817/#start_entry, accessed 25 September 2023. The archival record on Christopher McPherson is more extensive than what this data story covers.↩︎

Caio Simões de Araújo and Srila Roy, “Introduction: Intimate Archives: Interventions on Gender, Sexuality and Intimacies”, African Studies 81:3-4 (2022): 256.↩︎

An Ordinance, to Amend the Ordinance for Regulating Waggons, Drays and Carts, and for Other Purposes, 18 June 1810, in Petition of Christopher MacPherson to General Assembly, 10 December 1810, Legislative Petitions, Library of Virginia.↩︎

Müller, Escape to the City, 17, 20, 66.↩︎

Lex Heerma van Voss, “Introduction: Petitions in Social History”, International Review of Social History 46 (2001): 1–2; Andreas Würgler, “Voices from among the ‘Silent Masses’: Humble Petitions and Social Conflicts in Early Modern Central Europe”, International Review of Social History 46 (2001): 12, 32.↩︎

Bill of Rights (1791), Article the Third, National Archives (20 September 2022), URL: https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/bill-of-rights, accessed 25 September 2023.↩︎

van Voss, “Petitions in Social History”, 8.↩︎

Petition of MacPherson. McPherson had submitted an earlier petition to the Richmond City Common Hall on 3 August 1810.↩︎

Martha Jones, Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 1.↩︎

Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).↩︎

Sidney Blumenthal, A Self-Made Man: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln, 1809-1849 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014); Heike Paul, The Myths that Made America: An Introduction to American Studies (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2016), 367–407.↩︎

Petition of MacPherson.↩︎

Petition of MacPherson.↩︎

Edmund Berkeley, Jr., “Prophet without Honor: Christopher McPherson, Free Person of Color”, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 77:2 (1969): 186.↩︎

McPherson, A Short History.↩︎

Müller, Escape to the City, 60.↩︎

Population of Virginia—1810, URL: http://www.virginiaplaces.org/population/pop1810numbers.html, accessed 8 January 2019.↩︎

Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 185.↩︎

McPherson, A Short History; Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”.↩︎

Deed of Emancipation, David Ross to MacPherson (2 June 1792), Henrico County, Legislative Papers, Petition 5633, Library of Virginia.↩︎

McPherson, A Short History.↩︎

Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 185.↩︎

Petition of MacPherson. The constitution of Virginia of 1776 declared it to be a Commonwealth State.↩︎

Petition of MacPherson.↩︎

Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 185.↩︎

McPherson, A Short History.↩︎

Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 186; Petition of MacPherson.↩︎

Wolfe, “Christopher McPherson”.↩︎

McPherson, A Short History.↩︎

McPherson, A Short History.↩︎

Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 189.↩︎

Müller, Escape to the City.↩︎

McPherson, A Short History; Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 185.↩︎

Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 184.↩︎

Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 187.↩︎

McPherson did not detail his family situation. He had a daughter with his wife, an adopted son, and two more enslaved children from two enslaved mothers. Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 189.↩︎

Berkeley, “Prophet without Honor”, 187.↩︎

Müller, Escape to the City, 7, 68, 111.↩︎

David Zaret, “Petitions and the ‘Invention’ of Public Opinion in the English Revolution”, American Journal of Sociology 101:6 (1996): 1497–1555.↩︎

Nicholas P. Wood, “A ‘Class of Citizens’: The Earliest Black Petitioners to Congress and Their Quaker Allies”, William and Mary Quarterly 74:1 (2017): 109–144; Bianca Premo, The Enlightenment on Trial: Ordinary Litigants and Colonialism in the Spanish Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).↩︎

Rodney G.S. Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence”, Archivaria 61 (2006): 215-233; Jessica Marie Johnson, “Markup Bodies: Black [Life] Studies and Slavery [Death] Studies at the Digital Crossroads”, Social Text 36:4 (2018): 57–79; Amalia S. Levi, “Archives of Empires, Archives of Race: A Reflection on the 2023 Archives, Slavery & Race-Making Summer School”, dependency.blog (2 October 2023), URL: https://dependency.blog/archives-of-empires-archives-of-race-a-reflection-on-the-2023-archives-slavery-race-making-summer-school, accessed 2 October 2023.↩︎

Christian G. De Vito, Juliane Schiel, and Matthias van Rossum, “From Bondage to Precariousness? New Perspectives on Labor and Social History”, Journal of Social History 54:2 (2020): 649.↩︎

Petition of MacPherson.↩︎

Petition of MacPherson.↩︎

van Voss, “Petitions in Social History”, 2.↩︎

Amy E. Slaton and Tiago Saraiva, “Editorial”, History and Technology (14 November 2023), DOI: 10.1080/07341512.2023.2275357, accessed 21 November 2023.↩︎

Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 5.↩︎