Chains, Escapes and Debt Transfers aboard the Venetian Galleys

the case of Marco from Corfu

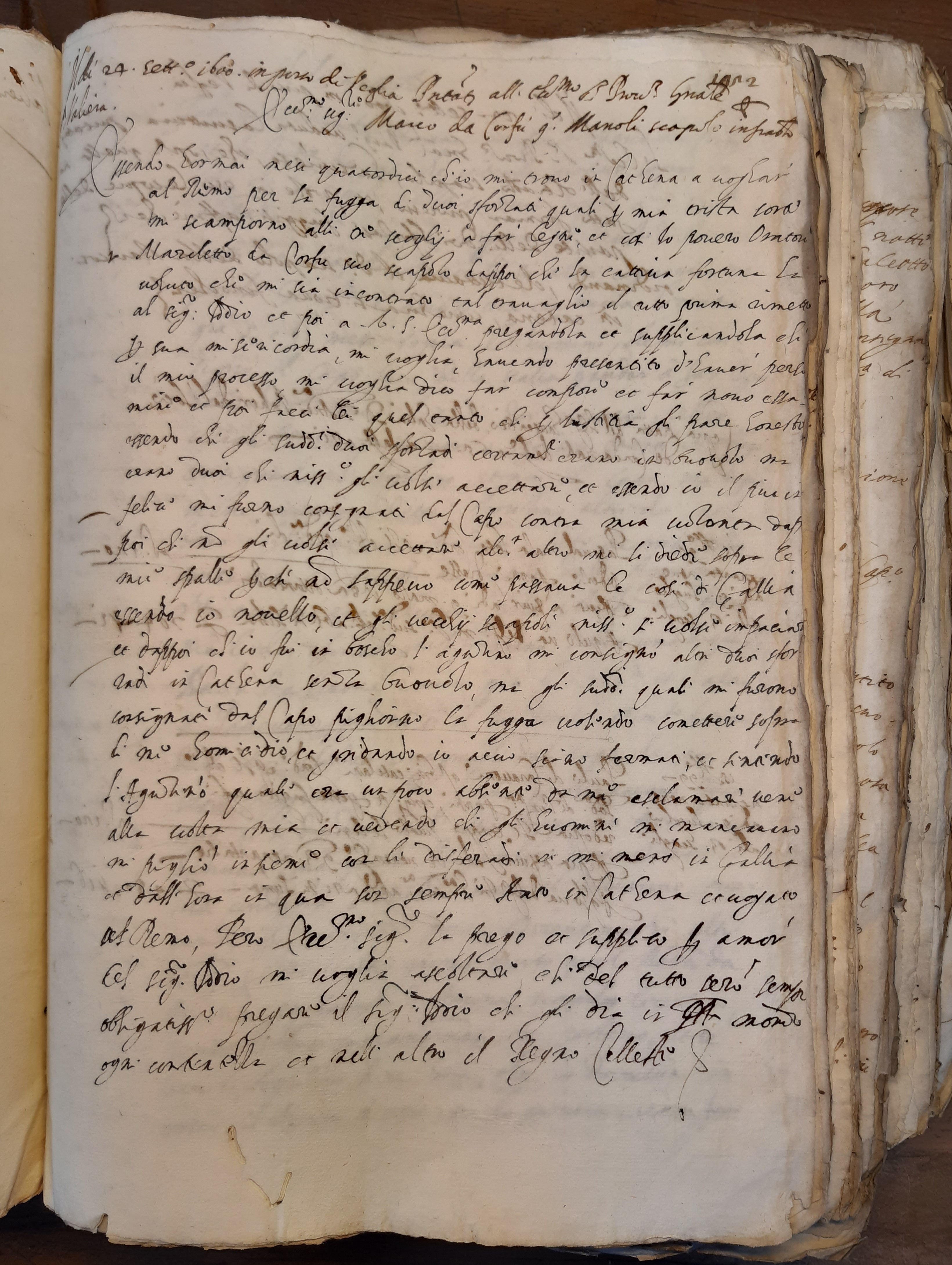

Trial number 12/23, conserved in the Cariche da Mar Processi fond (CMP, Frari archives, Venice), is a 19-page document written at the end of September 1600 about the escape of two galley convicts in the Venetian maritime colonies, the Stato da Mar. Trials of this kind were held aboard ships by the representatives of the Republic, generally called rettori, capitani or provveditori, operating within a military hierarchy and recording the voices of several thousand men working to maintain the scattered empire’s territorial coherence. Officials were granted exclusive means of coercion based on extraordinary, though temporary and ad hoc powers. This system was created to allow the military galleys to project Venetian power and to move effectively in the labyrinthine archipelagos of Dalmatia and Greece.1

This particular trial was formed by General Proveditor Filippo Pasqualigo in response to a request by Marco from Corfu. Marco, son of Manoli, was a former scapolo, or galley soldier, whose tasks were essentially to enforce security on ships, together with the aguzzini, tormentors, and prevent other galley men from escaping. Their presence fed the harshness of convicts’ daily life, but all galley men had the right to take legal action in the maritime courts, as Jean-Baptiste Xambo’s and Luca Lo Basso’s studies of the French and Genoese navies show.2This is why the document starts with Marco’s letter of supplication addressed to Pasqualigo:

(transcription)

‘Eccellentissimo Signor,

Essendo hormai mesi quatordici ch’io mi trovo in Cathena a voghar al Remo per la fugga di duoi sforzati quali in mia trista hora mi scamporno alli tre scogli à far legne, et cosi io povero Oratore Marchetto da Corfu suo scapolo dappoi che la cattiva fortuna ha voluto che mi sia incontrato tal travaglio il tutto prima rimetto al Signor Iddio et poi a Vostra Signoria Eccellentissima pregandolo et supplicandola che per sua misericordia, mi voglia, havendo presentito d’haver perso il mio processo mi voglia dico far compore et far novo essamination et poi facci lei quel tanto che per Iustitia gli pare honesto, essendo che gli suddetti duoi sforzadi certamente erano in buovolo ma erano duoi che nissuno gli volse accettare, et essendo io il piu infelice mi furno consignati dal Capo contra mia volonta dappoi chi non gli volsi accettare alcun altri mi lo diede sopra le mie spalle perche non sappevo come passava le cose di Gallia essendo io novello, et gli vecchi scapoli nissuno si volse impaciar et dappoi ch’io fui in boscho l’aguzino mi consignò altri duoi sforzadi in Cathena senza buovolo, ma gli suddetti quali mi furono consignati dal Capo pigliorno la fugga volendo comettere sopra di me homicidio, et gridando io accio siano fermati, et sentendo l’Aguzino quale era un poco absente da me esclamare vene alla volta mia et vedendo che gli huomini mi mancavano mi pigliò insieme con li disferadi et mi menò in Gallia et dall’hora in qua son sempre stato in Cathena et vogato al Remo. Pero Eccellentissimo Signor la prego et supplico per amor del Signor Iddio mi voglia ascoltare che del tutto serò sempre obligatissimo pregare il Signor Iddio che gli dia in prossimo momento ogni contentezza et nell’altro il Regno Celleste.’

(translation)

‘Very Excellent Sir,

It has now been fourteen months that I’ve found myself in chains manning the oar after the escape of two convicts, who escaped in my sad hour while we were cutting wood at the three rocks, and so I, poor orator Marchetto da Corfu, your scapolo, since misfortune has willed that I should be subjected to such hardship, I entrust everything first to the Lord God and then to Your Excellency, begging and pleading with you that, out of your mercy, you may let me compose and make a new examination, having heard that I would lose my trial, and then do as much as seems honourable in justice. Being that the two aforesaid convicts were certainly in buovolo, but they were two that no one wanted to accept, and since I was the most unfortunate, they were given to me by the chief against my will, and then the ones who did not want to accept them gave them to me over my shoulders because I did not know how things work on galleys, since I am a newcomer, and no one among the old scapoli wanted to take care of them. When I was in the woods, the guardian gave me two more convicts in chains without the buovolo, and those who were given by the chief escaped and wanted to murder me, and I shouted so that they could be stopped, and the guardian, who was somewhat absent, heard that I was exclaiming and came to me, and seeing that I was lacking men, he took me together with the disferadi and led me to the galley, and since then I have always been in chains and rowed at the oar. But most excellent Sir, I beg and implore you, for the love of God, will you listen to me, that I shall always be obliged to pray to God to give me much happiness in the near future and in the afterlife in the Celestial Kingdom.’

At first glance, the story told by Marco is very muddled. The first question is: Why is Marco rowing instead of fulfilling his position as a soldier? To understand this, we must delve into his story of labour coercion.

Wood cutting was considered among the worst forms of subjugations in the New World.3 The labour was physically exhausting if not brutalizing and often took place in remote areas to be conquered. In the Mediterranean, galley men were often put to work procuring wood supplies necessary to fix the hull and the oars, and sometimes that became an occasion to free themselves, as in the case of the two rowers mentioned by Marco. During the summer of 1599, while cutting wood in a forest ‘at the three rocks’, somewhere near the island of Krk (Veglia), he had been tasked as scapolo with supervising them. This was when he lost them.

After they deserted, Marco was put in chains to replace their loss; similarly, other CMP trials demonstrate that workers who were tasked with but failed to prevent other workers from escaping could be put in chains by authorities. This is especially common in relation to logging. Some convicts could make themselves piezzi, i.e. responsible or guarantors of other workers. The piezza allowed captains to charge these guarantors with the debt of those who escaped, even if they had nothing to do with the escape. At the time, however, the Venetians pushed the bureaucratic and judicial practices on board the ships, as illustrated by this kind of trials. I was unable to locate the document attesting to Marco’s conviction and his sentence to row, which must have been passed fourteen months earlier. One possible explanation is that his case had been handled in an informal manner.

Marco’s narrative is dense with details that can help us understand life aboard galleys: He mentions an important item, the buovolo, which could be the key to understanding his claim for justice. The difference between chains and the buovolo (also bovolo or branca) is that the latter is ‘a group of chains necessary to bind as many convicts as it takes to serve an oar in a galley’.4 On two occasions, he refers to these sorts of chains because he knew that the captains required the scapoli to use the buovolo to bind the convicts between them, to prevent escapes while on land. On board, convicts were tied directly to the ship with a different type of chain. Firstly, Marco had to accept supervising two convicts who were in buovolo (‘the two aforesaid convicts were certainly in buovolo’), and once in the forest, another guardian brings him two more men without the buovolo (‘the guardian gave me two more convicts in chains without the buovolo’). From his account, it appears that those who escaped were the latter, who were tied together and ran away together after either assaulting or threatening him (‘those who were given by the Chief escaped and wanted to murder me’).

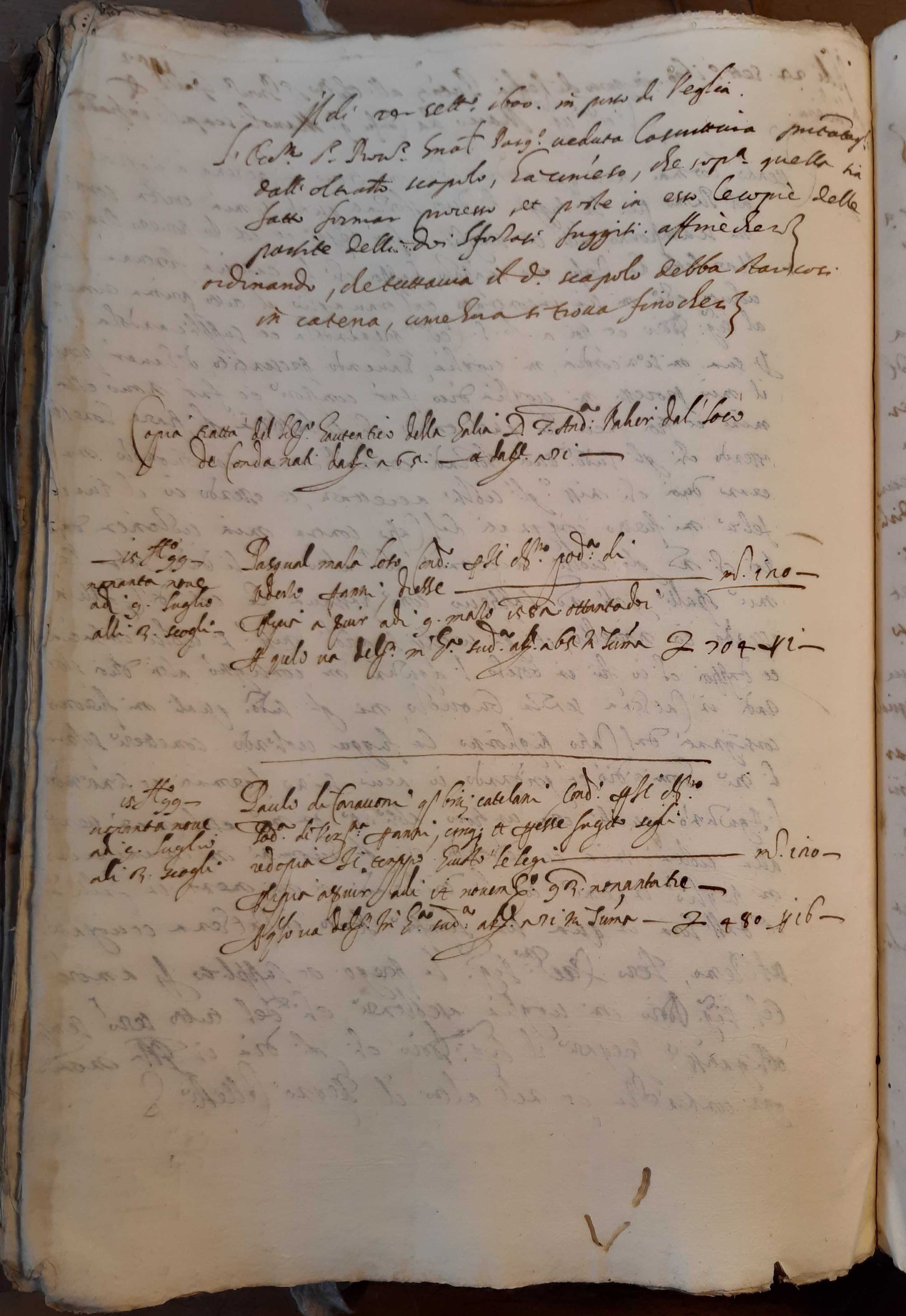

Beyond that, he mainly seems to point out the responsibility of other crew members. Marco styles himself as an inexpert galley worker: ‘they were given to me by the Chief against my will, and then the ones who did not want to accept them gave them to me over my shoulders because I did not know how things work on galleys, since I am a newcomer’. It appears that this is why the Proveditor decided to proceed with the trial: to verify whether others had any responsibility in this matter. In the trial record, the first thing Pasqualigo does is to obtain data about the two rowers who escaped, called Pasquale and Paulo. On the second page, we can see that Pasquale was condemned to row for ten years (‘per anni diese’) and Paulo for five years, a duration which was doubled following a previous attempt to escape (‘per anni cinque; et per esser fugito sigli redopia il temppo’).

Scribes writing on behalf of captains sometimes recorded the debts of workers when they deserted from their service. This document is a precious sample, enriched by Marco’s direct testimonials and scripts. The copy of the galley’s libro hautentico was necessary to evaluate precisely the loss caused by their escape, calculated in the form of their debts to their captain: Pasquale’s debts amounted to a total of 704 lire, and Paulo’s to 480 lire and 16 soldi.

The first man to be interrogated was Marco. He offers some names of possible witnesses; some dead, some dismissed, some still on board. One of them, Gieronimo from Padua, testifies that Marco, once he realized that Pasquale and Paulo had escaped, exclaimed ‘oh tell me!’ (‘ò poveretto mi’) and ran away to search for them. The most important testimony is that of the aguzzino, Antonio de Zuane from Venice. Knowing that it was forbidden to monitor four men at a time, he denies any responsibility, especially handing over two extra convicts to Marco once in the woods. He adds further weight by claiming that the scapolo was asleep during his guard duty. This detail is confirmed by other witnesses, such as Constantin from Crete. Stati from Corfu adds that there was a rumour that the two deserters were headed towards an Ottoman fortress, ‘Delvino Castello di Turchi’.

In the end, Captain Pasqualigo decided to divide responsibility for the escape between Marco and the aguzzino Antonio. Marco was ‘condemned to row the oar with chains on his feet in place of Paolin de Caravoni’. Antonio does not incur the oar sentence but is found liable for Pasqual’s escape and has to settle Pasqual’s debts out of his own pocket. He is also fined an additional sum of twenty-five ducats to be ‘deducted from Marco’s debt’ as a form of reparation ‘for [Antonio] having against orders handed over to the aforementioned scapolo the two convicts for the occasion of cutting wood.’ This tunes us in to the way labour on the galleys was commodified through debt. Debtors were registered as representing a more or less precise amount of money, which is supposed to be lost because of various escape practices.

At this time, galleys were still affected by Cristoforo da Canal’s reforms, inspired by his main treaty Della Milizia Marittima, which summed up the reasons for exploiting penal convicts in the public navy. These measures implemented the recruitment of convicts and debtors for the galee sforzate, which was instituted in 1545 as part of the military patrol of the imperial waters under his personal commandment.5 There is also a broader connection with anti-vagrancy measures in Western Europe6 imposing ‘civil death’7to ‘vagabonds’ who were still considered capable of working. Da Canal’s reforms indicated the need for the state to cut the navy budgets, stopping the Venetian tradition of waged work on galleys.8

H. Schlosser rightly suggested that observing galleys through the lenses of criminology (banditry, smuggling and vagrancy) had to be counterbalanced by the study of the jurisdictional exceptionality of galley sentences. This is true because maritime forced labour practices were studied based on trials on the mainland. However, trials aboard the ships show how much crime was inseparable from the law. The daily construction of the criminal enemy9 was managed internally and led to a constant superposition of social and jurisdictional aspects.

As in any relation of dependency, charging with debts has been a broad practice reflecting a will to criminalize the pre-industrial working class. It was also suggested that Venetian debtors could be the first people working in the navy for free.10 On board Venetian galleys, operating as colonial vectors of power along Istrian, Dalmatian, Albanian and Greek coasts, the same logic of bondage through debt was reproduced, with captains’ exceptional justice. A. Viaro once indicated that debts were the primary reason some workers found themselves rowing for 20, 30 or even 40 years.11

In an article dedicated to debts aboard galleys,12 historian Luca Lo Basso rightly argued that these debts were the ‘true cornerstone of the Venetian management system’.13 He defends the idea that at the end of the sixteenth century, patricians repudiated forced labour from a humanist, perhaps almost proto-Enlightenment perspective, which is the reason they began hiring waged workers again. However, coerced commodification of rowers’ labour is manifest throughout the period, as debtors were registered as if they represented a sum of money, which will be lost if they escape. Debts assigned on board and their transfer by judicial means prove the continuity of the logic of labour coercion: deferred judicial slavery, diluted in the accumulation of time still to be served.

As they appear in this and in many other trials, debts and escapes were two complementary phenomena crystallizing factually and synthesizing an otherwise hidden form of social conflict into a precise dialectical duality of labour im/mobility, respectively inside and outside the galleys: rejection of work results in even more severe work fixation.

Bibliography

Arbel, Benjamin. ‘Venice’s Maritime Empire in the Early Modern Period’. In A Companion to Venetian History, 1400-1797, edited by Eric Dursteler, 125–254. Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2013.

Boerio, Giuseppe. Dizionario Del Dialetto Veneziano. Venezia: A. Santini, 1829.

Geremek, Bronisław. ‘Renfermement Des Pauvres En Italie (XIV-XVIIe Siècle)’. In Mélanges En l’Honneur de Fernand Braudel, 1:205–17. Toulouse: Privat, 1972.

Linebaugh, Peter, and Marcus Rediker. The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon Press, 2000.

Lo Basso, Luca. ‘Il Mestiere Del Remo Nell’armata Sottile Veneziana : Coscrizione, Debito, Pena e Schiavitù (Secc. XVI-XVIII)’. Studi Veneziani, no. XLVIII (2004): 1–85.

———. ‘Lavoro Marittimo, Tutela Istituzionale e Conflittualità Sociale a Bordo Dei Bastimenti Della Repubblica Di Genova Nel XVIII Secolo’. Mediterranea. Ricerche Storiche XII, no. 33 (April 2015): 147–68.

———. Uomini da remo. Galee e galeotti del Mediterraneo in età moderna. Milano: Selene, 2004.

Melossi, Dario. ‘“The Prison and the Factory” Revisited (2017): Penality and the Critique of Political Economy Between Marx and Foucault’. In The Prison and the Factory (40th Anniversary Edition): Origins of the Penitentiary System, edited by Dario Melossi and Massimo Pavarini, 1–24. Palgrave Studies in Prisons and Penology. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Milani, Giuliano. ‘Banditi, malesardi e ribelli. L’evoluzione del nemico pubblico nell’Italia comunale (secoli XII-XIV)’. Quaderni fiorentini per la storia del pensiero giuridico moderno 38, no. 1 (2009): 109–40.

Pullan, Brian S. Rich and Poor in Renaissance Venice: The Social Institutions of a Catholic State, to 1620. Oxford: Blackwell, 1971.

Ruschi, Filippo. ‘Communis Hostis Omnium. La Pirateria in Carl Schmitt’. Quaderni Fiorentini per La Storia Del Pensiero Giuridico Moderno I diritti dei nemici, no. XXXVIII (2009): 1215–76.

Schlosser, Hans. Tre Secoli di Criminali Bavaresi sulle Galere Veneziane (secoli XVI-XVIII). Venezia: Deutsches Studienzentrum in Venedig/Centro Tedesco di Studi Veneziani, 1984.

Tenenti, Alberto. Cristoforo Da Canal: la marine vénitienne avant Lépante. Paris: SEVPEN, 1962.

Viaro, Andrea. ‘La Pena Della Galera. La Condizione Dei Condannati a Bordo Delle Galere Veneziane’. In Stato, Società e Giustizia Nella Repubblica Veneta: Sec. XV-XVIII, edited by Gaetano Cozzi, 377–430. Roma: Jouvence, 1980.

Xambo, Jean-Baptiste. ‘Servitude et droits de transmission. La condition des galériens de Louis XIV’. Revue d’histoire moderne contemporaine n° 64-2, no. 2 (21 September 2017): 157–83.

Footnotes

Arbel, ‘Venice’s Maritime Empire in the Early Modern Period’.↩︎

Xambo, ‘Servitude et droits de transmission. La condition des galériens de Louis XIV’; Lo Basso, ‘Lavoro Marittimo, Tutela Istituzionale e Conflittualità Sociale a Bordo Dei Bastimenti Della Repubblica Di Genova Nel XVIII Secolo’.↩︎

Linebaugh and Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic.↩︎

‘Un gruppo di catene che servono a legare tanti forzati che bastino al servizio d’un remo in galera .’ Boerio, Dizionario Del Dialetto Veneziano, 67.↩︎

Tenenti, Cristoforo Da Canal.↩︎

Geremek, ‘Renfermement Des Pauvres En Italie (XIV-XVIIe Siècle)’; Melossi, ‘“The Prison and the Factory”’.↩︎

Schlosser, Tre Secoli di Criminali Bavaresi sulle Galere Veneziane (secoli XVI-XVIII).↩︎

Pullan, Rich and Poor in Renaissance Venice; Lo Basso, Uomini da remo. Galee e galeotti del Mediterraneo in età moderna.↩︎

Milani, ‘Banditi, malesardi e ribelli. L’evoluzione del nemico pubblico nell’Italia comunale (secoli XII-XIV)’; Ruschi, ‘Communis Hostis Omnium. La Pirateria in Carl Schmitt’.↩︎

Viaro, ‘La Pena Della Galera. La Condizione Dei Condannati a Bordo Delle Galere Veneziane’.↩︎

Ibidem.↩︎

Lo Basso, ‘Il Mestiere Del Remo Nell’armata Sottile Veneziana’.↩︎

Lo Basso, Uomini da remo. Galee e galeotti del Mediterraneo in età moderna.↩︎