Introduction

In the Christian world of the European Middle Ages, two basic ideas on the organization of society became deeply intertwined: the biblical idea of sameness before God and the assumption of categorical difference and inequality inherent to the feudal estate system (Heinemann 1966: 8). This data story discusses the medieval conceptualization of society, social difference, and labor relations. It places the medieval sermon at the center of analysis. The sermon was the most important literary genre and “the primary means of mass communication during the entire Middle Ages in Europe” (Connell 2015: 1576, 1606). “Spoken in the voice of a preacher who addresses an audience,” it was essentially an oral discourse instructing and exhorting “on a topic with faith and morals and based on a sacred text” (Kienzle 2000: 151). While the form of a sermon remained discursive, the preacher mainly delivered a monologue upon which the audience was invited to reflect (Kienzle 2000: 152). The preacher spoke from a position of authority which allowed for the exercise of influence on the masses and projecting specific ideas. These included visions of society and social order preached to specific groups of people – as in the case of sermons “ad status” (Kienzle 2000: 152, 155; Muessig 2002: 255, 275–276). Sermons recorded in writing invite contemporary readers to reflect on the medieval doctrine of the estate system and of societal order in general.

The example chosen here is a sermon by Berthold von Regensburg, a well-known Franciscan preacher of the 13th century in the German territories. In the sermon entitled “From the Ten Choirs of the Angels and Christianity,” Berthold exposes his view of the world’s order. While his conceptualization of society and social difference builds on a long tradition having evolved since the times of St. Augustine (345–430), an in-depth analysis of the language and narrative structure used by the Franciscan monk helps to uncover the moral codes underlying medieval power and labor relations. Whether and in what way the specific dependencies outlined by Berthold von Regensburg can be characterized as coercive shall be part of the semantic analysis.

Chapter 1. Mendicant Orders: Preaching in the cities of 13th century Europe

Since the 11th century, the Christian world saw the emergence of numerous Christian groups, many of which pleaded for the return to a simpler lifestyle inspired by the vita apostolica. The plea, based on principles of renunciation, was often linked to a sharp critique towards worldly and religious leaders. These were accused of neglecting their duties as shepherds and heads of the Christian world, falling prey to the devil’s temptations of worldly pleasures. The Christian church considered many of these new groups dangerous and labelled them heretical. The mendicant orders, which emerged mainly in the 13th century, advocated an extreme ascetic lifestyle in accordance with similar principles of renunciation (Franziskus von Assisi 2009: 94–102). However, to counter the threat of rising heresies, the mendicant orders were authorized as part of papal policy (Heinemann 1966: 81). By making the mendicant orders an important carrier of reform from within the church, the papacy instrumentalized the critical impulse inherent in the apostolic lifestyle. This policy was fomented by Pope Innocent III (1198–1216), who approved the Ordo Fratrum Minorum (Order of Lesser Brothers), better known as the Franciscan Order, in 1209.

13th Century Mendicant Preachers in German Cities

Berthold von Regensburg (1210–1272) represents a new generation of 13th century mendicant monks who, rather than reflecting and writing on the divine and worldly order in the scriptoria of their monasteries, went out to preach the word of God to the people in the cities and the world. Unlike earlier monastic orders, the mendicants settled not only on the outskirts or outside larger villages and cities, but also in the city centers and at commercial intersections. The members of mendicant orders were not bound to the cloister where they made their vows (stabilitas loci) but were allowed to travel and move from one cloister and province to another. And instead of writing and preaching in Latin, the mendicants taught and reflected the Christian teaching primarily in the vernacular, the language of the people.

Until the 13th century, the prevalent episcopal attitude towards cities had been rather tainted. The clergy had construed cities as places of sin where worldly temptations festered freely, alluding to the biblical Babylon (Ertl 2008: 198–201). Many movements deemed heretical were in fact rooted in cities or at least attracted a great deal of their followers from them. It was therefore crucial for the church to expand its influence in the growing urban centers and win back the lay citizens. Both the Franciscan and Dominican Orders (the latter approved in 1216 by Pope Honorius III [1216–1227]) played a crucial role in this regard, as cities and their citizens became the main targets of their pastoral endeavors (Ertl 2006: 201–203).

The mendicant world order was based on an all-encompassing theological and philosophical system going back to Augustine. Fundamental to it was the hierarchical order of the cosmos, which interrelated all spiritual and worldly things. This idea also goes back to Augustine, although he clearly differentiates between the worldly and religious sphere in his famous De Civitate Dei. The two spheres coalesced into one unified divine order throughout the Middle Ages, reconciling the Christian idea of sameness before God with the inherent inequality of the estate system. This was crucial because the estate system provided the regulating framework for all social and political relations of the Christian community. The functional and organismic nature of the divine cosmos sought to unite the individual with the community. As part of an entity, each individual had his or her own God-given, community-oriented task. To carry it out guaranteed both perfect cosmic harmony and individual fulfilment and salvation. It was also essential that these individual tasks were willingly performed on the basis of love for God. Individual fulfilment therefore meant acceptance of one’s place and duty in the holy order of the cosmos (Heinemann 1966: 8–11).

A Wandering Voice of the Mendicant World Order: Berthold von Regensburg

This world order was spread across European cities through the many networks that the mendicants established. Preachers like Berthold von Regensburg played a crucial role in this process (Heinemann 1966: 80). Berthold, who joined the Franciscan order in 1226, was one of the most popular preachers of his time. According to reports by contemporaries, he enjoyed a charismatic and popular image and assembled huge crowds of listeners around him wherever he arrived. Born in Regensburg, he travelled as far as Paris and Prague, Zurich and Silesia.

Berthold established a wide network of contacts across Europe. One of his teachers was Bartholomäus Anglicus. Bartholomäus, himself a Franciscan, was the author of the encyclopedic work De proprietatibus rerum and taught in Magdeburg when Berthold was a student (Spätling 1953: 610; Röcke 1983: 235). In Magdeburg, Berthold also met David von Augsburg (~1200–1272), probably his most important companion. David von Augsburg was one of the first German-speaking members of the Franciscan order who worked in Magdeburg as novice master and accompanied Berthold on his preaching journeys through southern Germany. There is a collection of sermons that the two authored, which bears the name Baumgarten geistlicher Herzen(Orchard of Spiritual Hearts). David von Augsburg not only took an active role in the inquisition against the Waldensians (Audisio 1999: 7–10), but also dedicated himself to writing. His texts had a great influence on the Deutschenspiegel and Schwabenspiegel and were often copied and attributed to Bernard de Clairveaux or Bonaventura (Clasen 1957: 533–534; Röcke 1983: 235).

Another important companion of Berthold von Regensburg was the Dominican scholar Albertus Magnus (1200–1280). Albertus Magnus, one of the greatest intellectuals of the 13th century, was founder of the university of Cologne, head of the Dominican province Teutonia, teacher of Thomas von Aquin, and from 1260 bishop of Regensburg. Regensburg was financially and economically stricken at the time. Albertus Magnus was considered suitable for the rehabilitation and reconstruction of the diocese (Grabmann 1953:144). In 1263, Pope Urban IV (1261–1264) nominated Albertus together with Berthold von Regensburg to preach the crusade. Albertus and Berthold travelled throughout Germany and Bohemia to mobilize people for the crusade and reached as far as Paris, where they met King Louis IX of France (1214–1270) and Theobald II (1238–1270), the King of Navarre (Rosenfeld 1955: 164; Röcke 1983: 237, 256). Evidence of this meeting can be found in the Analecta Franciscana.

Even though Berthold as a person, his life, his travels, and his ideas found their way into many contemporary texts (such as the Sachsenspiegel), not many of his sermons (or their scripts) in Middle High German (Sermones in lingua vulgari) have survived. The 19th century philologists F. Pfeiffer and J. Strobl identified and edited 71 of Berthold’s vernacular sermons (Neuendorff 2000: 301–302). However, Jacob Grimm, another 19th century philologist, voiced disbelief that any of Berthold’s sermons known today were personally written by him. According to Grimm, his listeners or followers wrote down the sermons, probably even after his death. The question of authorship and/or to what extent these sermons were modified or edited is still discussed amongst scholars today (Neuendorff 2000: 303).

Chapter 2. Between Form and Essence: Ways of the Medieval Preaching and Berthold von Regensburg’s Sermons

In order to understand Berthold’s sermons, it is necessary to examine the historical background and the changes occurring in style and form. The homilia, which followed the patristic model of preaching and focused on the exegesis of fragments of the Scripture, was prevalent in the early Middle Ages. In the 13th century, a shift took place, leading from the homilia to the sermo. The sermo was a discourse based on a topic which derived from the Scripture (Roberts 2002: 43–44; Roest 2012: 383; Connell 2015: 1578). With the thematic sermon (also sermo modernus ), preachers employed a more complex structure, starting with a chosen theme and, as a next step, carrying out an analysis and explanation of the said theme with the help of subsections (Roest 2012: 383–384). The new style allowed for the inclusion and discussion of various issues, deriving mostly from theology, morality, or politics. The possibility of presenting various themes led to a further differentiation of the sermon thematically (Connell 2015: 1595–1596, 1608). At the same time, there was the so-called “homiletic revolution” of the 13th century, which embraced a new rhetoric of preaching (Roberts 2002: 45, 47, 51).

The changes in the High Middle Ages were not only rhetorical, but the composition of the audience also changed due to a shift from clerics to lay people. As the latter became more and more the audience of the preachers, efforts had to be made to make the sermons understandable. The audience determined the language used, with Latin sermons directed to the clergy and vernacular ones to the laity. The preacher had to use rhetorical means such as exempla, anecdotes, or wit to connect with the audience, whether Latin or vernacular speaking. As the High Middle Ages saw a rise in heretical groups, the call for popular preaching became more central to the Church and the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) stressed the importance of preaching. The sermon became the preferred medium by which religious doctrine was upheld and the education of the masses guaranteed, thus counteracting heretical beliefs (Roberts 2002: 44–45; Connell 2015: 1583, 1595, 1597–1598; Zajkowski 2010: 2077).

These changes also marked the style of preaching in 13th century Germany. The mendicants were crucial to the development and the practice of the sermo modernus , the most common of the new preaching styles (Johnson 2012: 8; Connell 2015: 1595; Ertl 2006: 112). Regarding the sermons given by mendicants, two types can be distinguished: the sermo ad monialium , also known as the cura monialium , and the sermo ad populum as the sermons preached to lay audiences (Schiewer 2000: 865–874). Among the sermons preached to the people, the sermo ad status was particularly popular and used when having to address a specific group of people (Muessig 2002: 255). Common topics related to salvation history, the call for and need of repentance, and to everyday situations and contemporary issues (Schiewer 2000: 868; Connell 2015: 1591, 1599; Heinemann 1967: 81). Although the Franciscans including theology, mystics, and philosophy in their preaching, the sermons were concrete enough for people to understand the content (Schmidt 1989: 295; Johnson 2012: 8). The Franciscan friars themselves advocated the new way of preaching by creating model sermon collections, other homiletic writings, as well as the artes praedicandi, i.e. manuals for the drafting and the rhetorical performance of the thematic sermon (Johnson 2012: 8; Roest 2012: 383). Stylistically, the thematic sermon was kept simple and was held in an emotional manner, turning simplicity and dramaturgy into essential components of early Franciscan preaching (Ertl 2006: 115; Connell 2015: 1596; Kienzle 2012: xii). Friars tended to preach in locations that were not only consecrated places such as churches, monasteries, and cathedrals, but more and more public and outdoor spaces, such as market crosses, public squares, or even fields, processions, and graveyards (Robson 2012: 274; Hanska 2002: 293; Kienzle 2002: 861). Eventually, the Franciscans were regarded as the correctores morum, and preaching grew into a fundamental part of their self-identification (Ertl 2006: 111, 113).

General Features of Berthold von Regensburg’s vernacular sermons

Berthold von Regensburg included several of these aspects of mendicant preaching into his own sermons. He preached both in Latin and in Middle High German. His sermons were of varying length; some are several pages long, others contain just a few sentences. He found inspiration for the main topics of his sermons in the Scripture. At the center of Berthold’s vernacular sermons are common people and everyday issues as a starting point for a general reflection on society and life in a community. The preacher’s aims were to guide people to live in a morally acceptable way, and to preach repentance for the people’s sins (Connell 2015: 1599; Schmidt 1989: 289). To achieve these goals, Berthold placed great emphasis on persuasiveness, concreteness, practicality, and understanding, which led him to resort to a simple and vivid style.

For the stylistics of his sermons, Berthold favored the ars praedicandi attributed to Bonaventure, which advocated the use of hyperboles, examples, and descriptions of the listeners’ everyday lives (Schmidt 1989: 290; Ertl 2006: 114–115). Berthold’s preaching style can be characterized as emotional, with fictitious dialogs, questions between preacher and listeners, and allegories (Röcke 1983: 240; Ertl 2006: 114; Connell 2015: 1599). The rhetorical techniques certainly contributed to his contemporary image as an influential and successful preacher (Ertl 2006: 115). However, readers of today cannot know how the listeners reacted to the highly stylized spoken word. The entire interaction between Berthold and his listening crowd cannot be deduced from the written sermons. This source-critical statement should be kept in mind for the discussion of the sermon selected for the in-depth analysis in this data story.

Overview of a Specific Sermon: “From the Ten Choirs of the Angels and Christianity”

The 10th sermon, entitled Die zehende. Von zehen körn der engele und der cristenheit. Simile est regnum celorum (The Tenth: From the Ten Choirs of the Angels and Christianity) is a sermo ad status directed at lay audiences. The sermon takes its point of departure from the Gospel according to Matthew (cf. Mt 13:44) and crafts a vision of society in which every estate is located; each has responsibilities to fulfil, while being legitimized and ordered by God.

There are several hierarchically interwoven levels in the 10th sermon. The basic division Berthold makes is between the himelrîche (“Kingdom of Heaven”) with is zehn koeren der heiligen engel (Ten Choirs of the Holy Angels), and the etrîche (Earth), also called nidern Himelrîche (lower kingdom of heaven), with its ten estates of people. The ten estates are further divided into the obern koere (upper choirs) and the nidern koere (lower choirs). The choirs are additionally numbered: the upper choirs were given the numbers one to three and the lower choirs were given the numbers one to six. The last estate is discussed separately.

Three groups of people constitute the upper choirs: 1) clergymen, 2) members of religious orders, 3) worldly judges, knights, and lords. Berthold von Regensburg places special value on these first three choirs, qualifying them as the hoehsten and hêrsten, respectively the “most sublime” and “most distinguished.” The lower choirs are divided in the following order: 1) people who make garments, 2) people who do their work with tools of iron, 3) people who trade, 4) people who offer food and drink for sale, 5) people who cultivate the soil, 6) people who practice healing. In Berthold’s vision of society, the tenth choir is the fallen one and includes the buffoons, violinists, and drummers.

In contrast to the “lower estates,” the members of the upper estates were personally assigned the activities and duties by God. The entire order of the estates is strongly oriented towards the needs of the upper choirs. The members of the first of the lower choirs must perform their services for the three upper choirs:

“Daz ist der dienst, den ir den drin hôhesten koeren schuldic sullet sîn.(…)”(“Your service, which you owe to the supreme choirs”)

Berthold von Regensburg also demands of the members of the 2nd lower estate that they serve the upper choirs as righteously as possible. The top three choirs depend on the services of the 3rd estate to be supplied with luxury goods via trade. The members of estates 4 to 6 of the lower choirs, on the other hand, are obliged to satisfy the needs of the whole society.

The preacher Berthold seems to regard work performance and the exchange of goods and services between individuals as essential to the functioning of society (Schmid 1989: 288). The social order had to be respected, as the following passage shows:

“Und er hat ieglîchem sîn amt geordent als ér wil, niht als dú wilt. Dû woltest lîhte ein ritter oder ein herre sîn, sô muost dû ein schuochsûter sîn oder ein weber oder ein gebûre, wie dich got danne geschaffen hât.” (“He has assigned to every human being his profession, as he wants it, not as you want it. You may want to be a knight or a lord, but you must still be a shoemaker, a weaver, or a farmer, just as God created you.”)

The social changes that resulted from the expansion of cities seemed difficult to reconcile with the striving for the salvation of the soul (Schmid 1989: 296). For the members of the various estates to fulfil their duties as a prerequisite for individual salvation, Berthold von Regensburg threatens them with apostasy from Christianity:

“Unde tuot ir des niht, sô sît ir the holy kristenheit aptrünnic worden unde man wirfet iuch in den grunt der helle zuo dem aptrünnigen engel.” (“If you do not, you have fallen away from holy Christendom and are cast to the bottom of hell to the apostate angel.”)

According to Berthold, everyone had an obligatory “work” to do, and all this was for God’s sake. The life and work of everyone in a Christian society are presented as a “God predetermined” matter, far from being a personal decision. Christians who move away from the predetermined tasks become “apostates.” After death, their souls go to hell.

Chapter 3. Semantic Observations on “From the Ten Choirs of Angels and Christianity”

Berthold’s “From the Ten Choirs of Angels and Christianity” is a sermon explaining the rightful societal order by using a binary language of incentives and threats. In order to uncover the moral codes and the specific character of – possibly coercive – dependencies underlying this social order, a semantic analysis of Berthold’s sermon was carried out through the computer-based annotation tool CATMA.

CATMA enabled an in-depth analysis of the text through its annotation- and text-mining tools. To make the most out of the program’s functions, we agreed on a set of categories based on previously defined research question. In the annotation process, the etic categories were constantly revised through the engagement with the source text. Tags were also created to categorize and regroup words and phrases. Since work and coercion are the two concepts which made up our research interest, they became our two main tags. The next step was to form adequate subtags to gain nuanced insight into the semantic composition of work and coercion in Berthold von Regensburg´s sermon. These subtags were mainly different syntactic categories, such as word types (nouns, verbs, etc.) in different inflected versions, with a greater focus on adjectives. Some subtags included semantic categories for which we already interpreted an underlying meaning, such as accusations and punishments. Another important subtag was the reference (to whom the word/phrase was directed to, either the first three estates, the estates four to nine, or to the tenth). This subtag became very important when analyzing the tags through cross-tagging, which was often used in the process of evaluating the results. It was also possible to determine the frequency, placement in the text, and collocations of words. CATMA also provided a tool to visualize these findings. Some of these graphs will also be shown in this chapter.

In the course of this analysis, we had to face several levels of translations. The analysis was based on the original text in Middle High German, but we frequently consulted translations into New High German in order to deepen our understanding of possible meanings. For the translation from Middle High German into New High German, we referred to the Standard German translation and edition by Röcke (1983), but also made use of Hepfer and Bachofer’s dictionary (2007). All references to grammatical structures are made on the basis of Berthold von Regensburg’s original wording in MHG. For this data story, we ourselves translated certain phrases into English, since the sermon as a whole has not yet been translated into English.

A Lexical Web of Dependencies: Adjectives, Verbs, and Nouns

In total, the sermon consists of 6,719 individual words in the original Middle High German edition (cf. Röcke 1983). In a first step, we looked at Berthold’s use of adjectives and adjectival structures as they relate to work and coercion. By utilizing dichotomic sets of adjectives, Berthold von Regensburg grammatically and semantically introduces the social composition of society, to which he adheres throughout the whole sermon. The use of obern/obersten (upper/uppermost) with 11 instances and nidern/nidersten (lower/lowermost) with 14 instances constitutes a clear baseline within Berthold’s Christian image of an ideal social order. These adjectives appear in a majority of cases as antecedents in noun phrases together with the substantives engel and koere. In addition, they are also used as nominalized adjectives to refer to the rank of a specific estate. Interestingly, a middle position between the two extremes – i.e., the top and the bottom of society – is missing, both semantically and content-wise. The fact that the adjective mittelsten (middle) appears only once may therefore reflect a lack of social mobility and penetrability of the rigid social system as proposed by Berthold. However, this has to be viewed with caution, due to the fact that we are not speaking about a post-industrialized social order with clear-cut classes.

A look at the work-related verbs further stresses the categorical distinction between the first three and the lower estates. This is best expressed by two predicatives that address the labor relation between estates. While the first three estates “owe” (schuldic sin) their work to the others, mostly accompanied with the prepositional phrase “because of their service” (umb ir dienst), the lower estates are unquestionably “subject” (untertaenic sin) to the upper estates without further explanation. Two things stand out from this observation. The first particularity is that those two adjectives (schuldic and undertaenic) have clearly distinct meanings. If someone “owes” something to someone it implies that the object of the sentence has already done something for the subject in the first place. This is strengthened through the annexed prepositional phrase “because of their service,” clarifying what exactly has been done for the upper estate for them to be obligated to return the favor. It is a justification of the obligation. Schuldic also relates to the notion of sin within the Christian worldview, and therefore provides a link between the earthly and the heavenly realm: Owing work or service to another estate mirrors the idea of owing atonement to God. In the context of the lower estates, the adjective undertaenic (subject) has a different meaning. Here, we find no trace of a specific “deal” that has been made. Rather, it designates a deadlock situation in which not only the obligation of fulfilling one’s designated duties is transported, but also the position and hierarchical relation. The second particularity is the use of these predicatives themselves. A predicative equates an adjective or noun to the subject (or object) of the sentence. That means that the adjective becomes part of the subject as a defining characteristic. The adjectives schuldic and untertaenic therefore become inherent traits of the respective social positions and their relations.

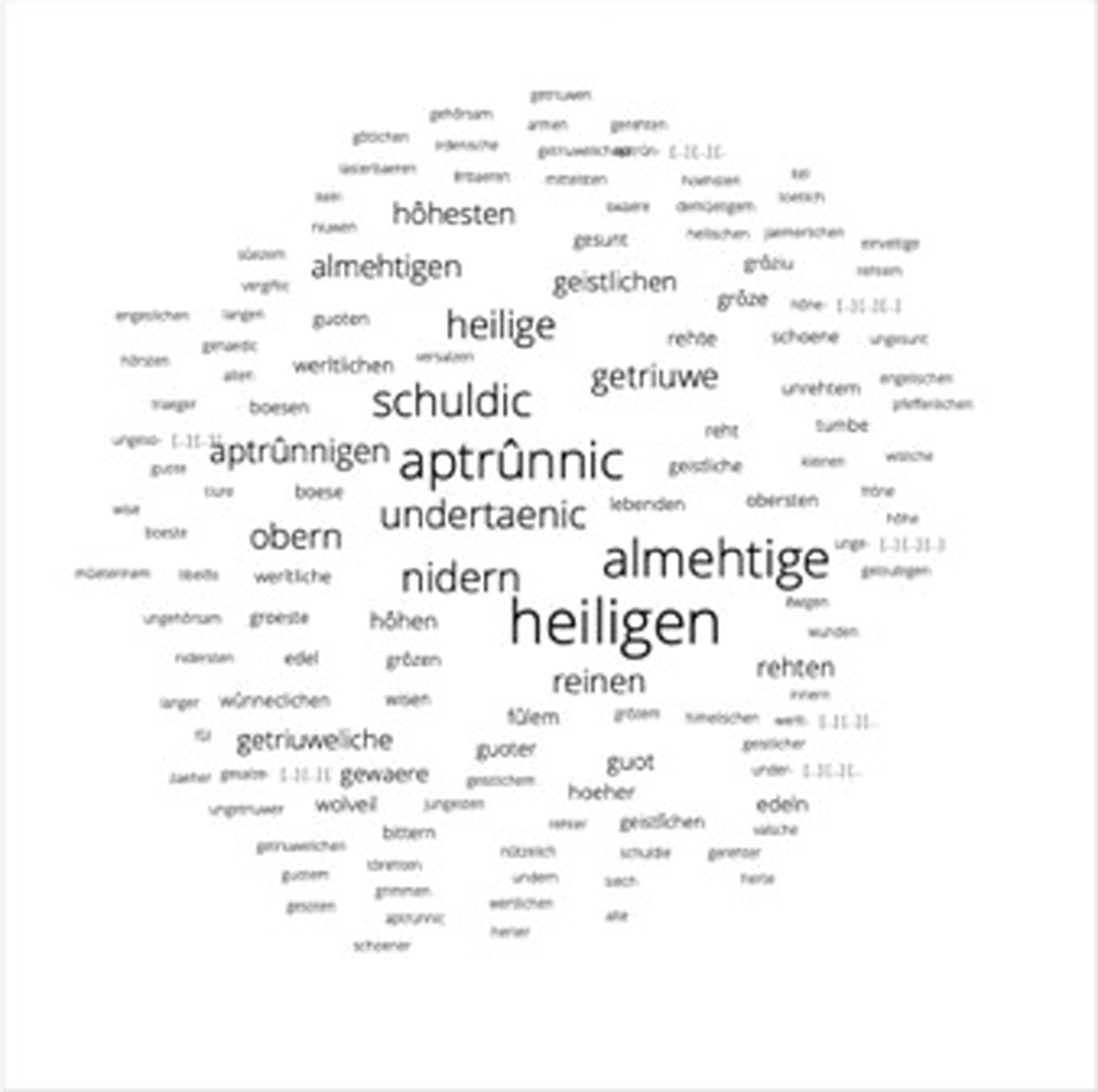

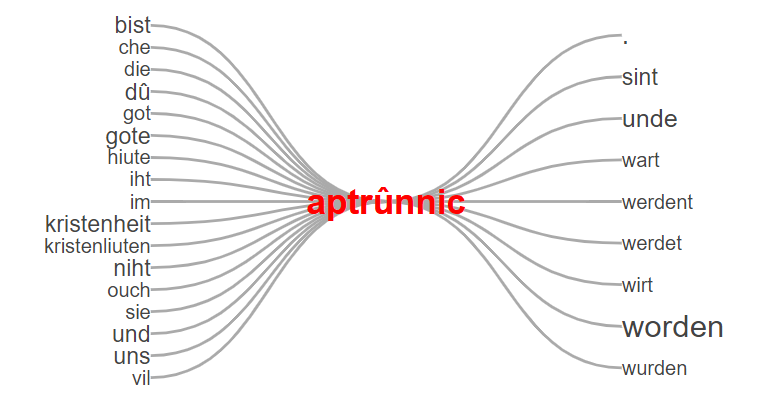

This also explains the frequency of schuldic and undertaenic, which together with aptrünnic / aptrünnige/r are the most frequently used adjectives. A general overview of all adjectives by frequency of use can be found in figure 1. The words aptrünnic / aptrünnige/r, schuldic, and undertaenic appear 32, 16, and 12 times in the sermon. Apart from the semantic relationship between the latter two, the third, aptrünnic, refers to the process of exclusion from any good social standing. Here, Berthold von Regensburg shows the vertical societal order of the angelic choirs as a model for humans. The societal standing is a direct result of one’s belonging to either the clergy or nobility. In absence of a person’s attachment to either group, their place in the social hierarchy is assessed based on their profession. Hereby the adherence to Christian teachings is crucial for the rank assigned to each profession. For example, gambling trades are excluded by virtue of their nature. Berthold von Regensburg establishes a trichotomy of the innate subservience of the lower ranked estates in society, which directly causes said estates to owe either service or labor to those higher up and could (if withhold) result in the individual’s spiritual demise – a concept referred to as being aptrünnic. Refusal to accept the God-given nature of this hierarchy and the obligations tied to it is ultimately punished by being confined to hell, this it is considered a renunciation of God Himself.

The high frequency with which aptrünnic, aptrünnige/-n, schuldic, and undertaenic are used in the sermon mirrors a Christian worldview that seeks to legitimize the existing status quo and the primacy of the Church and nobility as invested with their power by God. Semantically, these three adjectives and the corresponding concept of interdependent social groups are both theme and leitmotif of the sermon. The other adjectives of frequent use relate to the Bible and further demonstrate the role and importance of this reference text.

Besides the two verbal structures schuldic sin and untertaenic sin, there is a full verb used exclusively for the lower estates, which is “to serve” (dienen). This verb always refers to work that must be done for the upper estates. It establishes a hierarchy between the serving subject and the object of the sentence holding the semantic role of the benefactive: Dâ mite sult ir in dienen (With this you should serve them).

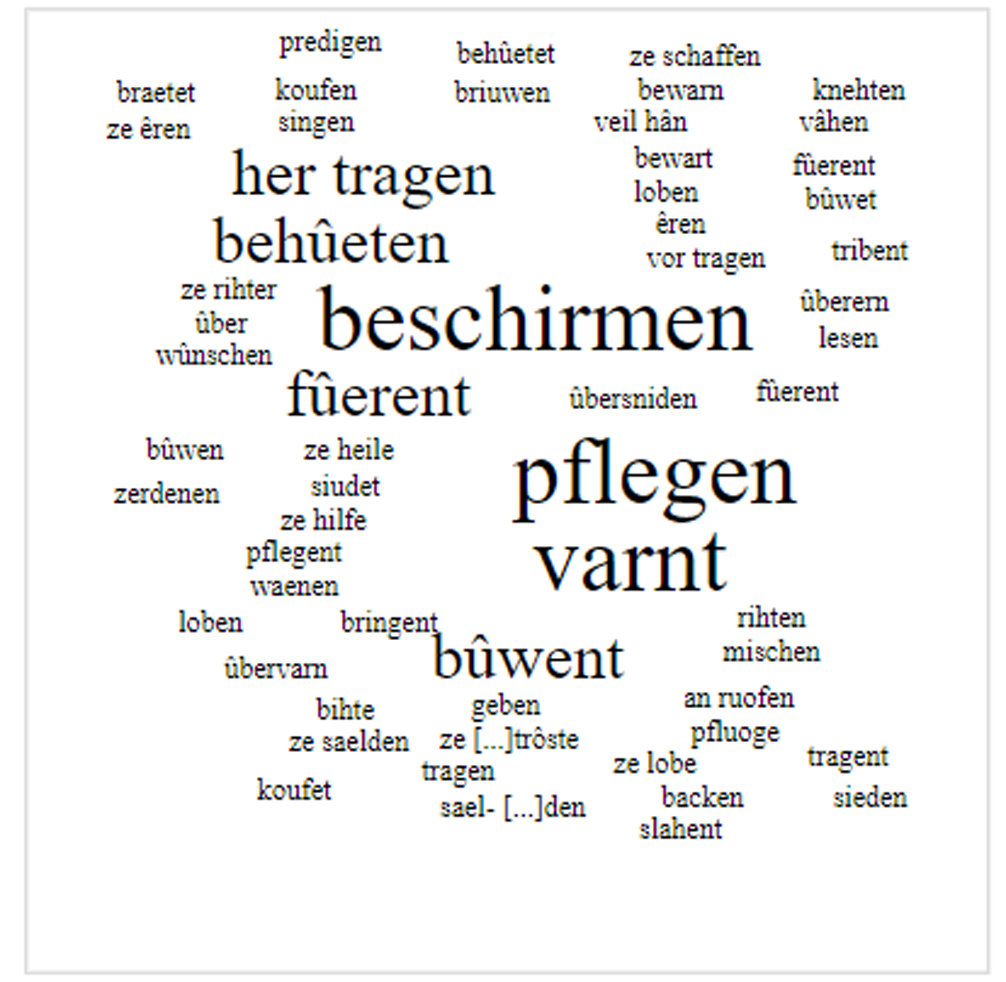

In addition to these three verbal phrases separating the upper from the lower estates, there is a variety of verbs describing the act of working, depending on who is doing the work and marking a separation according to the respective occupations. Thus, we see wirken only being used for those making clothes or working with iron. The verb üeben is seen in combination with the noun amt. Arbeiten as a verb is only used once in the context of people working with iron, combined with the participial adjective erbeitenden Manne. Schaffen is used once for the work God has given the third estate to do. This shows the semantically subdivided notations for different kinds of work. The variety of full verbs, which describe the specific activities of the different occupations, is presented in figure 2. The sermon therefore also gives insight into the diverse activities that were attributed to a specific estate, according to Berthold.

Translation (derived from the German translation in Hennig, Hepfer, and Bachofer 2007, own translation into English): pflegen (to take care of), varnt (to go / to ride), beschirmen (to preserve / to protect), fûerent (to lead / to carry / to bring), bûwen (to farm), behûeten (to protect / to preserve), singen (to sing / to write poetry), êren (to praise), rihten (to dispense justice / to enact laws), briuwen (to farm), tragen (to carry), tribent (to drive [load animals]), wûnschen (to wish for), sieden (to surge / to cook), loben (to comfort), backen (to bake), siuden (to cook), waenen (to hope), *mischen (to mix), koufet (to buy), lesen (to read), trôsten (to comfort), bringen (to bring / to create), heilen (to heal), ruofen (to call), predigen (to preach), pfluoge (to plough), hilfen (to help), zerdenen (to stretch), bihten (to confess).

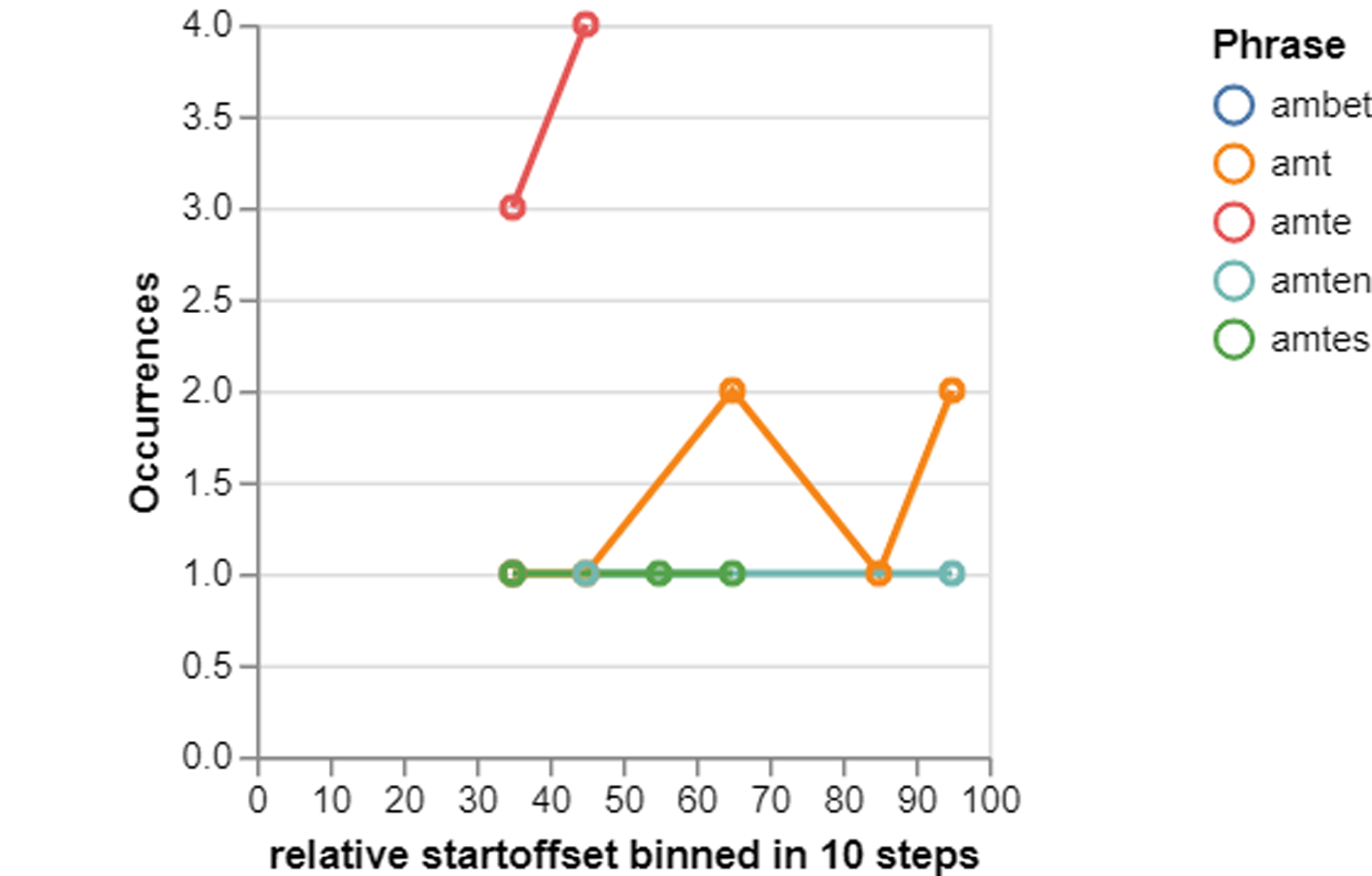

The nouns in the context of work can be regrouped into two categories – those that are generic terms referring to work in general and those that are used as “job titles,” so to say. For the first category, the words amt (occupation, profession), dienst (service), kôr (choir), gesinde, and werk (work, craft, etc.) are found in different declined forms. These nouns are introduced only when talking about the occupations of estate four to nine. This can be seen in figure 3, where the term amt is only used when Berthold is describing estates four to ten.

The nouns are semantically distinct and vary in their frequency and contexts. Amt is the most frequent term and mostly used together with kôr to connect the term with the metaphorical meaning of being part of a certain sacred order that resembles the angels’ order in heaven. Amt is also used to interlink the people that are doing the same work under one defining term. The word can therefore also be seen as a binding element through which different people who share one occupation have a connecting commonality. In this sense, it is used to differentiate between occupations, to connect them to the biblical analogy, and to create a togetherness within a certain working group. This identity-creating character also becomes noticeable through possessive pronouns such as iuwre (your), ir (their), and dine (your), which are antecedents of these terms and always refer to the estates four to ten.

Dienst is also commonly used and is mostly, except for a single occurrence, collocated with one of the predicatives schuldic sin or untertaenic sin. It can be understood as the work one is obligated to do, which is linked to the working relation and the dependency under which this works needs to be done. This is also phrased like that in the sermon “Sô gibest dû dinen dienst” (“so you give your service”). The noun Dienst is mostly found in prepositional phrases combined with the said predicatives schuldic sin umb den dienst(to owe someone a service) or undertaenic sin mit dem dienst” (to be subservient through service). Werk is only found when Berthold is talking about the estate that works with iron and is used only once referring to God´s work. Gesinde is also used only once, but addressing the fifth estate. Kôr is found a couple of times to refer metaphorically to work, with the same meaning as amt, and is meant to highlight the sacred order under which these hierarchies are formed.

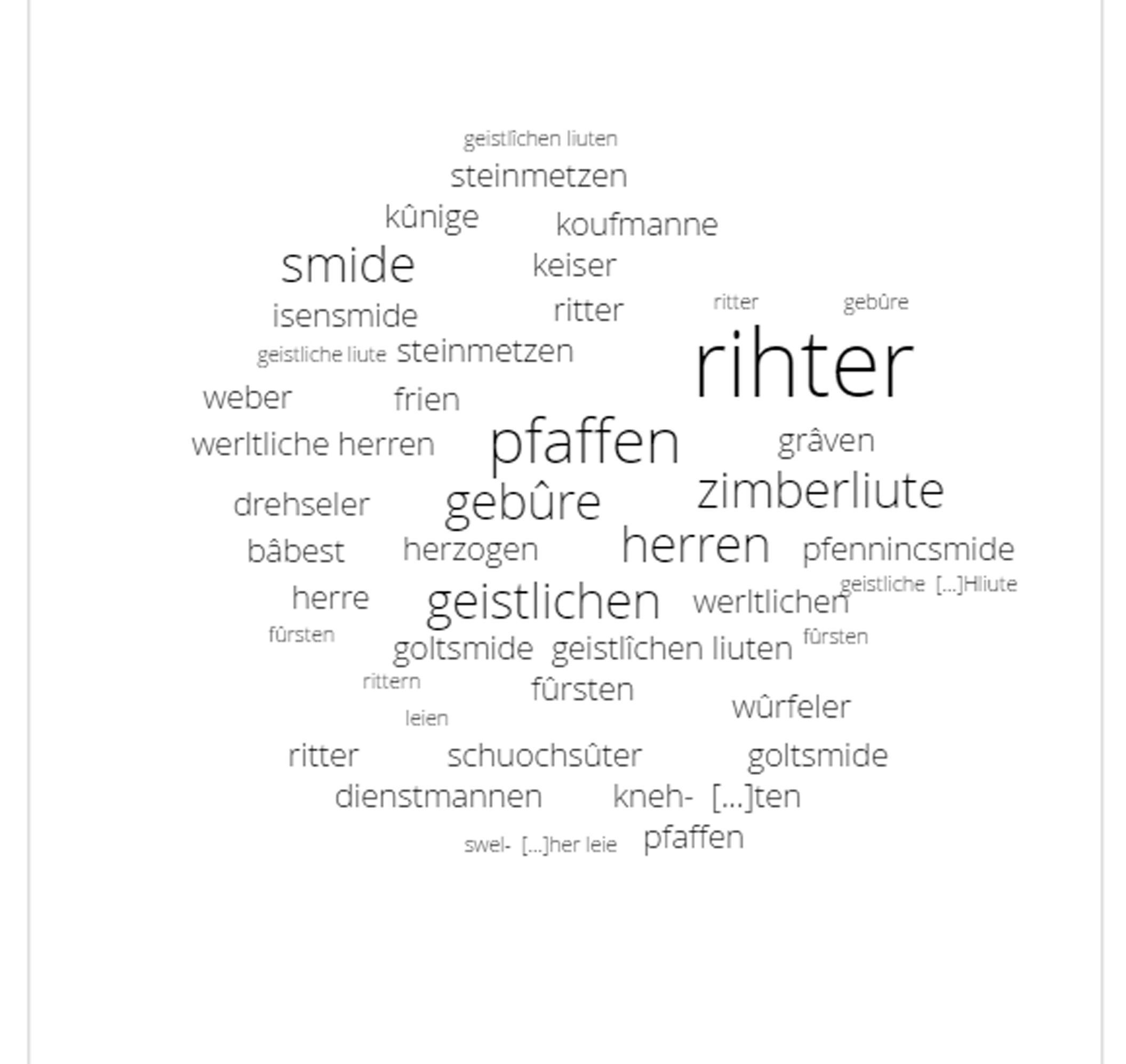

The other nouns in the sermon are “job titles,” names referring to activities of work that a group of people does. These can be found in all the estates and are exemplarily represented in figure 3. The growing number of these different professions can be seen in line with the acceleration of urban development. They also provide hints about who the target audience of Berthold’s speech might have been, as we find very detailed job descriptions, and a variety of the professions addressed were mainly found in the urban centers. This can also be understood as an attempt to incorporate the urban milieu into the Christian world order, as demonstrated in chapter two.

Translation (derived from the German translation in Hennig, Hepfer, and Bachofer 2007, own translation into English): Rihter (judge), pfaffen (priests), werltliche herren (worldly sovereign / lords), smide (smith), zimberliute (carpenter), geistliche liute (clerical people), gebûre (peasants), bâbest (pope), steinmetzen (stonemasons), wûrfeler (dicer), goltsmide (goldsmith), knehten (servant), fûrsten (duke), ritter (knight), pfennincsmide (coin smith), drehseler (drechsler / turner), keiser (emperor), graven (count), dienstmannen (ministerial), weber (weaver), koufmanne (merchant), isensmide(blacksmith), schuchsûter (shoemaker), frien (baron), kûnige (kings).

To sum up, the semantics of work found when analyzing the verbs and nouns in Berthold von Regensburg’s 10th sermon can be understood to further differentiate the work and working relations between the upper and the lower estates as well as to define the occupations created within them. Whether through biblical analogies or the different verbs, adjectives, and nouns used, the emphasis is on justifying a specific order under which work must be done. By doing that, the variety of work activities and the groups of people who fulfil it become visible as well. The occupation serves as a defining element through which people are related to each other under one amt and become part of Christianity.

Mechanisms of Coercion in Berthold’s Conceptualization of Social Order

In a final step, we now reflect on mechanisms of coercion identifiable in the language of this penitential sermon. The main element of coercion is found in the omnipresent threat of being excluded from the community of Christianity and sent to hell if one’s God given position in the social order is not respected. The semantic analysis of the sermon reveals several narrative layers through which this form of coercion is articulated.

The first form is the articulation of orders. Orders appear frequently throughout the sermon and can be differentiated in (a) direct orders most commonly expressed in direct speech (i.e., ir sult, which translates as “you shall”) and (b) instances when Berthold refers to divine orders. When referring to divine orders, Berthold uses the verbs bevolhen (9x) and geordent (23x). The modal verb sullen/süllen (shall or should) also occurs frequently throughout the sermon and is often used in combination with verbs referring to the duties of the whole Christendom or certain estates, as well as to specific working activities, as seen in figure 2. Moreover, sullen appears in reference to the aforementioned expressions untertaenic sin and dienen, giving a coercive character to these ascribed tasks. Sullen (and its various derivative forms) is used in reference to all the estates. Grammatically, the verb appears in the third person when Berthold talks about the upper estates (sô sullent sie uns behûeten / “so they shall protect us”), and in the second person or in combination with the indefinite pronoun man (one) when addressing the entirety of the Christian community (usually in the context of direct duties towards God, such as sol man got unde sine heilige muoter loben / “one shall praise God and his holy mother”). Other frequently used modal verbs are müezen and mûgen. Müezen is only used for the earthly estates, i.e. the lower estates and the third estate of the upper estates, but in this context only once; mûgen is exclusively used for lower estates.

The second way of articulating coercion is through the use and juxtaposition of the moral concepts triuwe (loyalty, allegiance) and trügener (cheater). Triuwe represents a key concept in Middle High German literature, referring to the fulfilment of duties both in social relations among humans and in the relation between Man and God. In Berthold’s sermon, triuwe and its antonyms appear 38 times throughout the sermon, taking on ten different grammatical forms. The adverbial getriuwelichen occurs as a descriptor of how work is supposed to be performed. Interestingly, its opposite appears frequently in direct speech, when Berthold directly addresses those who he considers dishonest in performing their labor: phrases such as Dû ungetriuwer velscher (“You disloyal forger”) or Pfi, verrâter, ungetriuwer! (“Disloyal traitor!”) operate as accusations and could possibly aim at instilling shame or guilt, while signaling the consequences of dishonest work. The way in which one serves has severe implications for one’s whole person (becoming a disloyal cheater), and therefore it can also be argued that it has a coercive function.

The use of the antonym aptrûnnic is especially interesting as it illustrates the constant parallels drawn between the earthly and the heavenly spheres. Within the context of the Lucifer narrative, aptrûnnic is used to describe the angels of the tenth choir, who are excluded from the community of Christianity and “have joined the devils, where there is no salvation for those people.” A closer look reveals that the word most commonly appears jointly with the verb werden (to become), forming a predicative, as seen in figure 5. Being apostate, then, can be understood as something one becomes because of one’s actions, rather than an inherent characteristic, as seen before with the predicatives schuldic sin and undertaenic sin. This implies that apostasy is a state that can be avoided through acting rightfully – although Berthold is not quite clear on its irreversibility, as he addresses the possibility of remorse and penance. Again, the idea that everyone has been assigned a specific place in society by God is central. Any attempt to deviate from one’s assigned role is considered disobedience of the divine order, and will be punished:

“Unde swâ ir des niht tuot, so sit ir dem almehtigen gote aptrûnnic worden unde sit gevallen ûz der gemeinde der heiligen kristenheit (diu gelichet sich dem wûnneclichen himelriche): die wirfet er zuo den aptrûnnigen engeln” (“And if you do not act accordingly, then you have become apostate to the almighty God and have fallen from the community of holy Christianity [which resembles the glorious heaven]: he will throw them to the apostate angels”).

Primary Sources Cited

Franziskus von Assisi. 2009. “Bullierte Regel, Lateran, 29.11.1223.” In Zeugnisse des 13. und 14. Jahrhunderts zur Franziskanischen Bewegung, edited by Dieter Berg, 94–102. Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker.

Röcke, Werner. 1983. Berthold von Regensburg. Vier Predigten: mittelhochdeutsch – neuhochdeutsch. Stuttgart: Reclam.

List of References

Audisio, Gabriel. 1999. The Waldensian Dissent. Persecution and Survival, c.1170–c.1570. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berg, Dieter. 1986. “Bettelorden und Bildungswesen im Kommunalen Raum. Ein Paradigma des Bildungstransfers im 13. Jahrhundert.” In Zusammenhänge, Einflüsse, Wirkungen, edited by Joerg O. Fichte, Karl Heinz Göller, and Bernhard Schimmelpfennig, 414–425. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Blastic, Michael W. 2012. “Preaching in the Early Franciscan Movement.” In Franciscans and Preaching: Every Miracle from the Beginning of the World Came about through Words, edited by Timothy J. Johnson, 13–40. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Clasen OFM, Sophronius. 1957.”David von Augsburg.” In Neue Deutsche Biographie 3: 533.https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118679007.html#ndbcontent.

Connell, Charles W. 2015. “The Sermon in the Middle Ages.” In Handbook of Medieval Culture: Fundamental Aspects and Conditions of the European Middle Ages, vol. 3, edited by Albrecht Classen, 1576–1609, Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

“David von Augsburg.” n.d. Bistum Augsburg website, https://bistum-augsburg.de/Heilige-des- Tages/Heilige/DAVID-VON-AUGSBURG.

Ertl, Thomas. 2008. Religion und Disziplin. Selbstdeutung und Weltordnung im frühen deutschen Franziskanertum. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Grabmann, Martin. 1953. “Albertus Magnus.” In Neue Deutsche Biographie 1:144–148. https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118637649.html#ndbcontent.

Jordan, William Chester. 1979. Louis IX and the Challenge of the Crusade: A Study in Rulership. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hanska, Jussi. 2002. “Reconstructing the Mental Calendar of Medieval Preaching: A Method and its Limits: An Analysis of Sunday Sermons.” In* Preacher, Sermon and Audience in the Middle Ages*, edited by Carolyn Muessig, 293–315, Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Heinemann, Wolfgang. 1966. “Zur Ständedidaxe in der deutschen Litertaur des 13. – 15. Jahrhunderts.” Beiträge zur deutschen Sprache und Literatur 88, no. 1: 1–90.

Hepfer Christa, and Wolfgang Bachofer. 2007. Kleines mittelhochdeutsches Wörterbuch. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Johnson, Timothy J. 2012. “Introduction: The Franciscan Fascination with the Word.” In Franciscans and Preaching: Every Miracle from the Beginning of the World Came about through Words, edited by Timothy J. Johnson, 1–12, Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Kienzle, Beverly Mayne. 2000. “Introduction.” In The Sermon, edited by Beverly Mayne Kienzle,143–174. Turnhout: Brepols.

Kienzle, Beverly Mayne. 2002. “Medieval Sermons and their Performance: Theory and Record.” In Preacher, Sermon and Audience in the Middle Ages, edited by Carolyn Muessig, 87–124, Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Kienzle, Beverly Mayne. 2012. “Foreword.” In Franciscans and Preaching: Every Miracle from the Beginning of the World Came about through Words, edited by Timothy J. Johnson, xi–xv. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Layher, William. 2009. “‘She was completely wicked’: Kriemhild as exemplum in a 13th-Century Sermon.” *Zeitschrift für deutsches Alterthum und deutsche Literatur *138, no.2:344–360.

Michaelis, Beatrice. 2011. (Dis-)Artikulationen von Begehren: Schweigeeffekte in wissenschaftlichen und literarischen Texten. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Muessig, Carolyn. 2002. “Audience and Preacher: Ad Status Sermons and Social Classification.” In Preacher, Sermon and Audience in the Middle Ages, edited by Carolyn Muessig, 255–276. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Neuendorff, Dagmar. 2000. “Bruoder Berthold sprichet – aber spricht er wirklich?: Zur Rhetorik in Berthold von Regensburg zugeschriebenen deutschen Predigten.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 101, no. 2:301–312.

Rasmussen, Jørgen Nybo. 1992. “Die Bedeutung der nordischen Franziskaner für die Städte im Mittelalter.” In Bettelorder und Stadt. Bettelorden und städtisches Leben im Mittelalter und in der Neuzeit, edited by Dieter Berg, 3–18. Werl: Dietrich-Coelde-Verlag.

Roberts, Phyllis B. 2002. “The Ars Praedicandi and the Medieval Sermon.” In Preacher, Sermon and Audience in the Middle Ages, edited by Carolyn Muessig, 39–62. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Robson, Michael. 2012. “Sermons preached to the Friars Minor in the Thirteenth Century.” In Franciscans and Preaching: Every Miracle from the Beginning of the World Came about through Words, edited by Timothy J. Johnson, 273–296. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Röcke, Werner. 1983. “Nachwort.” In Berthold von Regensburg. Vier Predigten, edited by Werner Röcke, 235–264. Stuttgart: Reclam.

Roest, Bert. 2012. “‘Ne Effluat in Multiloquium et Habeatur Honerosus’: The Art of Preaching in the Franciscan Tradition.” In Franciscans and Preaching: Every Miracle from the Beginning of the World Came about through Words, edited by Timothy J. Johnson, 381–412. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Rosenfeld, Hellmut. 1955. “Berthold von Regensburg.” In Neue Deutsche Biographie 2:164. https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd11851007X.html#ndbcontent.

Schäfer, Joachim. n.d.. “Artikel Albertus Magnus” In Das Ökumenische Heiligenlexikon. https://www.heiligenlexikon.de/BiographienA/Albertus_Magnus.htm.

Schäfer, Joachim. n.d.. “Artikel Urban IV.” In Das Ökumenische Heiligenlexikon. https://www.heiligenlexikon.de/BiographienU/Urban_IV.html.

Schiewer, Hans-Jochen. 2000. “German Sermons in the Middle Ages.” In The Sermon, edited by Beverly Mayne Kienzle, 86–961. Translated by Debra L. Stoudt. Turnhout: Brepols.

Schmid, Joachim. 1989. “Arbeit und soziale Ordnung. Zur Wertung städtischer Lebensweise bei Berthold von Regensburg.” Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 71, no. 2:261–296.

Schürer, Markus. 2011. “Die Beredsamkeit des philosophus celestis. Predigt und Rhetorik bei den Medikanten des 13. Jahrhunderts.” In Cum verbis ut Italici solent natissimis. Funktionen der Beredsamkeit im kommunalen Italien/ Funzioni dell’eloquenza nell’Italia comunale, edited by Florian Hartmann, 41–66. Göttingen: V&R unipress.

Spätling OFM, Luchesius. 1953. “Bartholomäus Anglicus.” In Neue Deutsche Biographie 1:610. https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd119098709.html#ndbcontent.

Zajkowski, Robert W. 2010. “Sermons.” In Handbook of Medieval Studies: Terms – Method – Trends, vol. 1, edited by Albrecht Classen, 2077–2086. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter.