Court records about the labour movement and the everyday life of the working poor in interwar Thessaloniki

In this paper I will discuss how court records can act as a portal to social history, the history of everyday life and the history of labour and the labour movement. In my extensive research in inter-war Thessaloniki's judicial archives I classified and studied the entire material of the summaries of the minutes of the Local Criminal Court of First Instance in the years 1922-1923 and 1932, years of crisis and extreme poverty. My data story here present incidents related to violations of Labour Law, strike struggles and labour conflicts, communist activity and other episodes in the daily life of the working poor. Two cases translated from Greek accompany the paper and serve as examples of the type and character of the information drawn from the relevant archival material.

The Court Archives: The Research

The Criminal Court of First Instance was reserved for misdemeanours, offences, for which prison sentences and fines of medium severity were provided by the Criminal Code. Its archive contains an extremely wide range of offences such as smuggling, unlawful possessions of weapons, forgery, obscenity, vagrancy, libel, promotion to prostitution, wounding, arsons, unjust assaults, insults against citizens or government officials, fraud and theft, but also breach of labour law and breach of the "Idionymo" (4229/1929), as the Greek law is called that in 1929 established anticommunism as an official state ideology, criminalising not only communist activity but also communist propaganda.1 The archive does not include any detailed pleadings, extensive defence statements or testimonies, but only brief summaries of each case, making "snapshots of tensions" even more tiny.2

Violations of Labour Law

In quantitative terms, violations of Labour Law concern an extremely small percentage of all cases. Specifically, the 1932 Single – Member Court File identifies 60 employers for violation of labour laws. This is 1,7% of the total, whereas 52% of the cases involved insults and assaults. Although laws introducing labour legislation were passed from the early 1910s, to secure - as has been pointed out - working class consent for military involvement in the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and in the First World War, there had been little improvement in real life working conditions. The corps of labour inspectors was permanently understaffed, while the eight-hour law which was voted in 1920 actually involved very few sectors of labour.3

In relation to violations of working time laws, the archive reveals mainly the tricks used by employers to illegally extend working time. Examples of missing clocks or tables with weekly days off are rather typical. When they came before the court, however, the employers were usually acquitted. In 1932, 38 of 41 employers accused of violating working hours were acquitted.4 Typical of another dimension of exceeding working hours is the case in which Athanasios Milakas, the owner of a tobacco factory was denounced in April 1932 for employing workers for more than eight hours. He did not deny it. However, as the inspecting officer noted, these were workers who had been hired on a "contractor's flat-rate basis", on a project contract.5 The practice of subcontracting, of flat-rate work, was spreading beyond employment in the craft industry, despite the opposition of the labour movement. Violations were certainly more numerous, workers did not seem to trust the judiciary to denounce their employers. Particularly in Macedonia and Thessaloniki, the control of labour legislation, due to understaffing of the labour Inspection Body, was assigned to the police. The police officers, apart from lacking training, were not particularly determined in controlling employers. They were the same people who were responsible for the repression of the labour movements.

Strike struggles and labour conflicts in the judicial archives

At first glance, the number of workers brought to court for their participation in the labour movement is even smaller than the number of employers accused of violating labour laws. Specifically, for violation of Law 2111 "On Freedom of Labour", which passed in 1921, when the workers’ anti-war reactions against the Asia Minor Campaign became more radical, only three cases can be identified in 1923 and 16 in 1932.6 A closer look at the archive reveals, however, the extent of social tension caused by the sharpening antagonisms between capital and labour in this period. Some 30 percent of the 316 cases involving insults and attacks on police officers relate to arrests of workers at illegal worker meetings or occupations of workplaces by unemployed workers. On January 29, 1932, six unemployed workers were brought to court for violently attacking a policeman. They had been prevented from attending a municipal soup kitchen in their neighbourhood because of their political views. They were punished with one month's imprisonment.7

Clashes between strikers and scabs – strikebreakers, communists and fascists, are also recorded in cases that are referred to in the archives as insults and attacks (often armed attacks) against citizens in working-class neighborhoods and politically marked cafes. In May 1932, members of the fascist organisation National Union Hellas (EEE) "left the booths bloody… they came out, assembled in fours, fired into the air and left, with military step" after attacking with weapons a "nest of communists" in a café in the refugee district of Triandria.8

Communist activity and the court records

Anti-communism was the official state policy, the unifying national idea, after the defeat of the "Great Idea", the nationalist expansionism in the Greek-Turkish war. Although we have several studies that analyse the rationale of the basic anti-communistic law, the "Idionymo", based on official legal texts and the press, the court records allow us to deepen the research, as they capture what was prosecuted in practice. In the archive, in the year 1932 a total of 121 defendants are identified, 115 men and six women. From them 75 were sentenced to a combination of prison and exile for an average of two years. The indictments outline the repertoire of communist activity. They also identify the planning and actions based on important dates and anniversaries of the interwar communist movement. August 1, the "Day against War", the "Day of Internationalist Action", March 25, the day of celebration of the Greek Revolution and May Day. On March 25 in the refugee district of Toumba, outside of the sport union's "MENT" offices, Savvas Adamtsiloglou, 19 years old, a textile worker and "notorious communist" and Eftsratios Doukas, 21 years old, a private employee, refugee from Istanbul, were arrested for possession and distribution of anti – war leaflets of the Communist Youth of Macedonia-Thrace. They were sentenced on July 30 to 18 months in prison and six months exile on the barren island of Anafi.9 With particular frequency the decisions concern communist activity in the army. Rizospastis, the newspaper of the Communist Party, was often persecuted for texts of similar content, and more often the Jewish communist newspaper, Avanti. The significantly higher percentage of cases of violation of the Idionymo Law, than other relevant violations, shows the identification of communist politics with labour-union activity and the authorities' choice of harsher punishment for struggling workers.

Other cases on the daily life of the working poor

The archive contains a wealth of further information about the daily life of the working class at work and in the neighbourhood. In the thousands of cases of insults and assaults that are hosted in the archive, extreme diffuse social tension or "a war of all against all" is described. The reasons for the interpersonal quarrels had to do with the lack of infrastructure, with the unbearable lack of drinking water and sewage facilities, which were lacking in the roughly constructed working-class neighborhoods. The State, by intervening as an arbitrator in the daily tensions of the poor, was shifting its own responsibility, its own inadequacies to the conflicting opponents in the slums.

The archives also records sexual violence against mainly young girls and boys in the workplace and in the job search process. In 1932, the case of a domestic workers' employment agency which was involved in trafficking networks was revealed in considerable detail. After being seduced by colleagues, bosses or foremen, young girls of working-class origin often seem to have ended up in brothel rooms from which they were only allowed to leave with the permission of the Vice Department of the Police. The court record enables us to trace the context of this special confinement.

The archive also provides a glimpse into the parallel or illegal economy in the city. In the neighbourhoods of Thessaloniki, especially in the small rooms of the refugee settlements, it seems that a tobacco processing network had been set up, linked to the smuggling networks and tobacco producers outside the city. The above network, survival theft, and other expression of the informal economy provide answers to how the popular classes survived in the interwar period when cost-of- living studies comparing wages and commodity prices usually reach a dead end.

In conclusion

The archive provides glimpses of ordinary people caught in moments of transgression, conflict, tension or bad luck. Working in the archive is like working under a microscope, as Arlette Farge mentions. What is said, what is recorded is certainly mediated. It aims at acquittal or conviction. It is possibly often a lie. But it draws on what is socially and culturally available and in this sense it approaches truth, opening a window to History from Below, a history of ordinary people, a history of the low strata. Judicial archives contain rich data and different perspectives on social and labour coercion. The archive becomes more talkative when cases that do not at first seem to be linked to the field are included in the survey, when we "flip" the archive and don't follow the official classifications. The theatre of the courtroom reproduces scenes of everyday life, confirming knowledge and suspicions but also opening the gaze both to the banal and unusual everyday life, focusing the perspective on moments of crisis, moments of drama, moments of condensation that potentially allow us to better understand the values, attitudes, ideas and practices of the working poor.10 Through the court records we can try to hear the voices of the silenced, the people of the working classes, the rebellious, the compromised or the marginalised. But we can also see beyond their voices, ideas, cultures and representations. We can, as Carlo Ginzburg has pointed out,11 also reach out to the material world, learn more about the social and economic context, deepen our analyses and study the various aspects and causes of social tension together with the history of labour and the labour movement.

Appendix: Examples from the Three Member Criminal Court of Thessaloniki, 1932

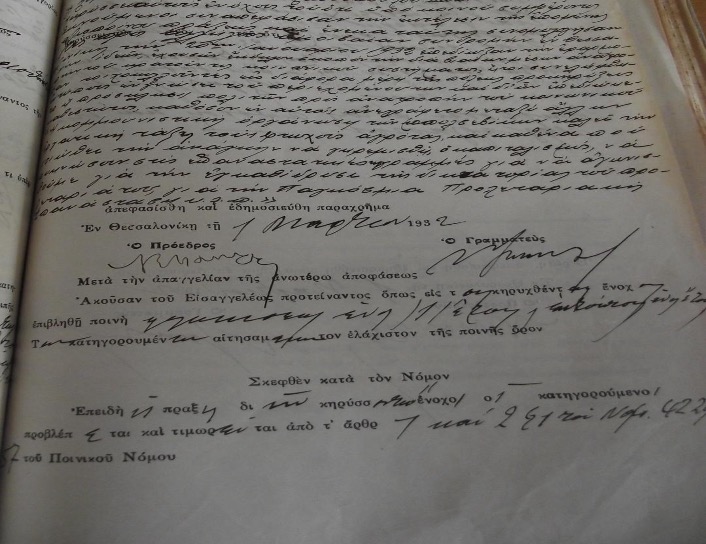

According to court decision n/a 983 of 1 March 1932 of the Thessaloniki Local Criminal Court, (Three Member Plenary Court), two men, 25 and 32 years old, waiters of refugee origin, were arrested in Thessaloniki for violation of Law 4229/1929. This was the law that punished communist propaganda and action. The accused were sentenced to one year in prison and one year in exile. Here is the ending part of the court decision:

were arrested in 20 January 1932 for posting in various parts of the city printed leaflets with the knowledge of their content and seeking to call on citizens to overthrow the social regime, since they stated, among other things, that the Bolshevik communist organisation was calling on the working class, the poor peasants and everyone who feels the need to overthrow capitalism to join the revolutionary ranks to fight for the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, for the World Proletarian Revolution, etc.

General State Archives, Historical Archive of Macedonia, Judicial Records, Three Member Plenary Court, 1 March 1932, decision 983.

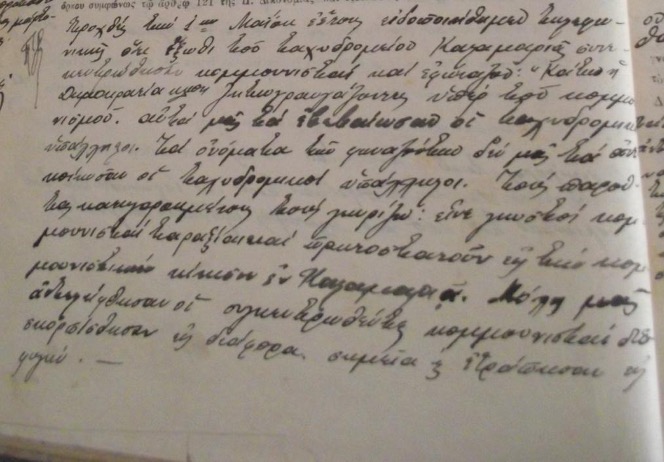

Decision n/a 1952, 3 May 1932 concerning the conviction of three workers for participation in the May Day events in the workers’ quarter of Kalamaria in Thessaloniki. All three were of refugee origin, aged between 19 and 30, and were listed as a painter, a salaried accountant and an unskilled worker. They were sentenced to one year and six months in prison.

A police officer involved in the arrest testified as a prosecution witness:

Τhe day before yesterday, May 1st of this year, at about 11 am, the postal clerk […] informed us that communists gathered outside the post office of Kalamaria district, cheering for communism and shouting against the Army, against Democracy etc.’ Immediately then I rushed to the spot with the gendarmes and as soon as they heard us they scattered to various addresses and fled. The three accused present were discovered by me at the head of the assembled communists. They are well-known communists who form the core of the communist activity in Kalamaria. The first one we arrested him outside the post office at that moment and the other two later, and this was because they were caught and left.

Footnotes

General State Archives (GSA), Historical Archive of Macedonia (IAM), JUS. 1.05, Archive of the Criminal Court of First Instance, decisions n.a. 4001-8017, 1923 ∙ 1-7857, 1932 (Single-member Court), 1-8339, 1932 (Three-membered Court, 1-5539. Judicial records were the main primary source of my research for my doctoral thesis: Konstantinos Tziaras, Τα λαϊκά στρώματα στη Θεσσαλονίκη του Μεσοπολέμου: Κοινωνική και Πολιτική διάσταση της φτώχειας, [The low strata in Thessaloniki during the Interwar Period. Social and Political Dimension of Poverty], PhD thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki 2017.↩︎

On the "snapshots of tensions" in judicial records see Arlette Farge, Η γεύση του αρχείου, [The taste of the Archive]transl. Ρίκα Μπενβενίστε, Νεφέλη, Athens 2004, p. 23.↩︎

Efi Avdela, «Αμφισβητούμενα νοήματα: Προστασία και αντίσταση τις Εκθέσεις των Επιθεωρητών Εργασίας 1914-1936» [Contested meanings: Protection and Resistance in the Reports of the Labour Inspectors 1914-1936], Τα Ιστορικά, vol. 15, 28-29, (June - December 1998), 171-202.↩︎

On employers’ practices of extending working time in textile factories see Leda Papastefanaki, . Εργασία, τεχνολογία και φύλο στην ελληνική βιομηχανία. Η κλωστοϋφαντουργία του Πειραιά, 1870 – 1940, [Work, technology and gender in Greek industry. The textile industry of Piraeus, 1870 – 1940], Πανεπιστημιακές Εκδόσεις Κρήτης, Irakleio 2009, p. 324-327.↩︎

Single Judge Court, n.a. 2711, 9 April 1932.↩︎

About the law 2111 see Anastasis Ghikas, Ρήξη και ενσωμάτωση: Συμβολή στην Ιστορία του εργατικού – κομμουνιστικού κινήματος του Μεσοπολέμου (1918-1936), [Rupture and integration: a contribution to the history of the interwar workers’ - communist movement] Σύγχρονη Εποχή, Athens 2010, p. 110-117.↩︎

Single-Judge Court, n.a. 596, 29 January 1932.↩︎

Single Judge Court, n.a 6497, 22 October 1932.↩︎

Three Member Court, n.a. 3397, 30 July 1932.↩︎

Farge, The taste of the Archive, ibid, p. 24-25, 44-49, 94-96, 116.↩︎

See the introduction in Carlo Ginzburg, Ο δικαστής και ο ιστορικός. Σκέψεις στο περιθώριο της δίκης Σόφρι [The Judge and the Historian. Reflections on the margins of the Sofrio trial], Νεφέλη, Athens 2003.↩︎