Transferring Land and People

The Muslims of Çenet, Sagra, and Agna and the Military Order of Santiago (1341)

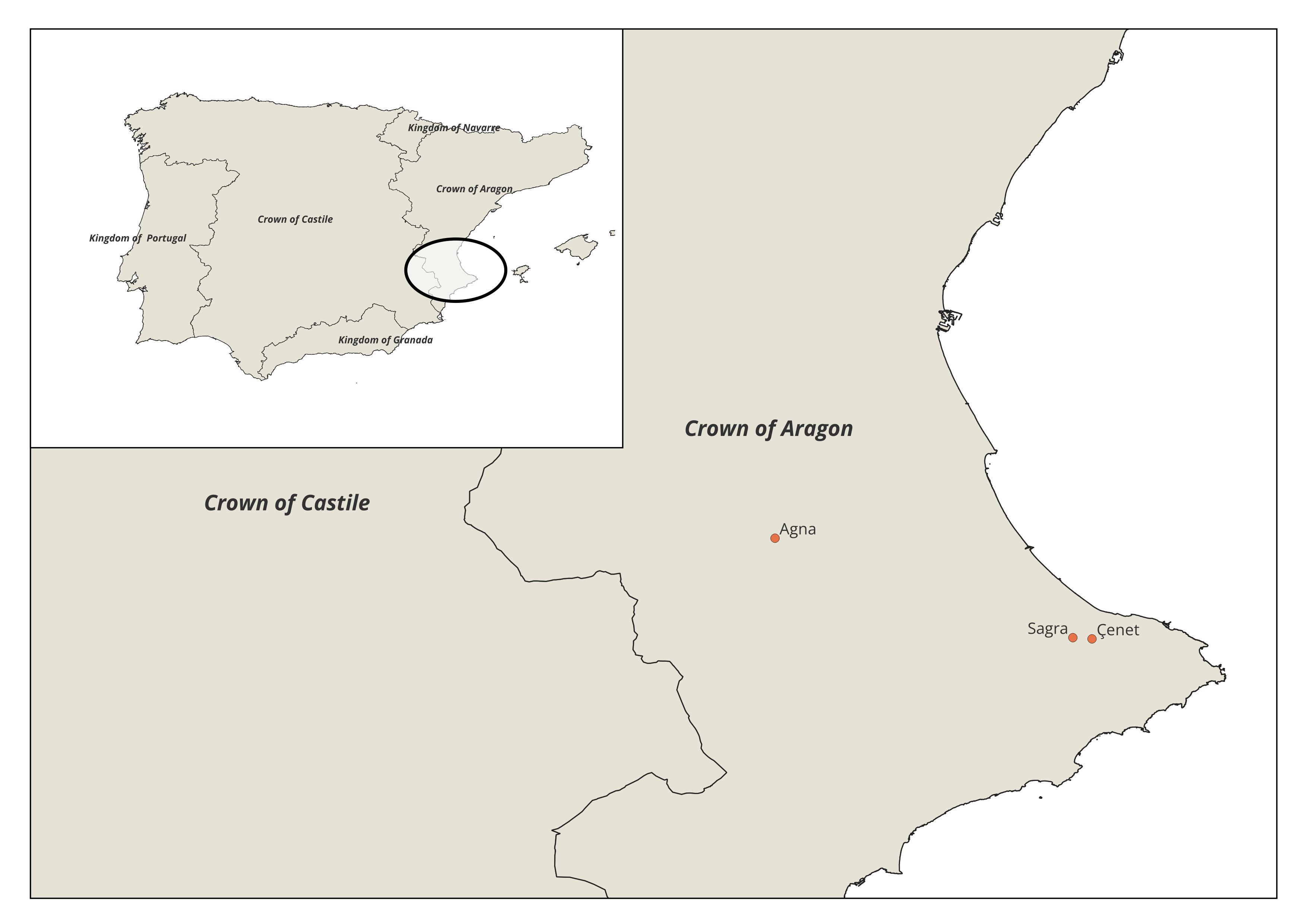

This data story explores the language and structure used in charters related to the establishment of relations between Muslim subjects and Christian lords during the Middle Ages.1 It does so by analysing a specific charter issued when a village and its Muslim inhabitants changed lordship within the Kingdom of Valencia in 14th-century Iberia.

The goal of this analysis is twofold: Firstly, it presents a fascinating case study of Muslims entering a relationship of dependence with a military order in medieval Iberia. The second aim is to apply a historical semantics approach to the written record of this event. In doing so, the article will focus on the structure of the text and the action phrases contained in it.2Action phrases are to be understood as “coherent continuous grammatical compound[s] describing an ‘action’” of any sort.3

The dataset

The document at the centre of this analysis is a charter from 1341 that codifies the transfer of lordship over the village of Çenet to the Order of Santiago.4 It is part of dataset comprising four written charters relating to a single transaction by which the order exchanged two villages for a third with a nobleman named Pedro de Villanueva in 1341.5 All three of these villages were located in the Kingdom of Valencia.

The earliest document in the dataset is an agreement reached in July 1341 between Pedro de Villanueva and representatives of the military order to make an exchange involving several settlements.6 In this arrangement, the Order of Santiago granted to Pedro de Villanueva the settlement of Agna (today: Anna, in the province of Valencia) and received in exchange the village of Çenet (today: Senat i Negrel) as well as the neighbouring Sagra (both in the province of Alicante), which had both belonged to Pedro de Villanueva up to that point.

The other three documents pertaining to the transaction were issued in September of 1341 and documented the change in lordship for each of the three affected villages.7 One charter was drawn up for each of the three settlements included in the agreement. They describe the ceremony accompanying the transfer of the villages and the homage paid by their Muslim inhabitants as a sign of their submission to their new lords. From these charters, we learn that despite being given to the Order of Santiago as per the agreement, the settlements of Çenet and Sagra temporarily remained under the lordship of Pedro de Villanueva (during his own life as well as that of his heir).

The charters are preserved as original parchments. They were kept in the archive of the Order of Santiago until its ultimate dissolution in the 19th century, whereupon they were incorporated into the National Historical Archive in Madrid; they have remained there to this day in the “Military Orders” section. Since the agreement of July 1341 still has the original seals attached to it, it was eventually moved to the “Sigilography” section of the archive to facilitate its preservation.

Out of these four documents, the following analysis will focus on the one relating to the transfer of lordship over the village of Çenet along with its Muslim inhabitants. It was issued on 17 September 1341 to codify the terms of the exchange agreed a few days before. Its structure and wording are very similar to those of the charters relating to Sagra and Agna, which were issued on the same day respectively two days later. Two copies of the charter were created and validated, one to be given to the representatives of the Order of Santiago and the other to Pedro de Villanueva, as stated explicitly at the end of the document. The validation of the charter does not include any Muslim witnesses, nor did the Muslim community receive a copy of the document.

Text structure and action phrases

The charter is focused on how the Order of Santiago took over the village of Çenet and its Muslim inhabitants, describing the change of lordship between Pedro de Villanueva and the order. This is reflected both in the structure of the text and in the key action phrases contained in it.

Accordingly, the first section of the text after the initial protocol is dedicated to recounting the terms of the agreement drafted between the two lords on 14 July and codified in the earliest charter in the dataset.

The central and most extensive part of the document provides an account of the ceremonies performed by the representatives of the Order of Santiago to take possession of their new property. It is in this section that the Muslim inhabitants of Çenet appear in the proceedings. When they do, it is to submit to their new lords and swear fealty to them, as well as to promise the fulfilment of their fiscal obligations.

The third and final section of the charter records the value of the village. This is done by asking representatives of the Muslim community (the leader of the Muslim community and the person in charge of collecting revenue for the lord) as well as Christian authorities involved in collecting revenues in the past (the bayle and the rector of a nearby parish) for confirmation of the income the village generated.

The charter ends with a final protocol detailing the form of validation along with the number of copies and witnesses, and featuring the sign of the notary providing the validation.

Of these sections, the most interesting for this analysis is the central one describing how the representatives of the Order of Santiago took possession of Çenet.

First, Pedro de Villanueva transferred the houses of Çenet by handing over the keys to the representatives of the order and leading them inside. He thus ceded physical ownership of the village, as indicated by the use of the verb entregar (to give, to deliver).

Entregó el dicho don Pedro de Villanueva a los sobredichos procuradores de unas casas del dicho logar de Çenet con todos sus términos e pertenençias ... e entregó les las llaves de las dichas casas e tomólos por las manos e púsolos dentro en las dichas casas.

(“Pedro de Villanueva gave to said representatives some houses of that village with all their lands and possessions, and gave them the keys to said houses, and took their hands and led them inside said houses.”)

The section relating to the Muslim inhabitants of the village begins after the representatives of the order have carried out this first physical ceremony for the takeover. Their actions form part of the implementation of the exchange agreed between Pedro de Villanueva and the Order of Santiago, in a similar way that the action phrases relate to the transfer of the village itself and its possessions. The sentence construction also reflects this.

Pedro de Villanueva, who had owned the village up to this time, ordered (mandó) all Muslim inhabitants of the town to gather and recognize the Master of the Order as well as the institution itself as their lords from that moment onwards. In this way, the actions signifying the beginning of the relationship between the Muslim inhabitants of Çenet and the Order of Santiago are framed as a response to a command from their lord rather than occurring of the settlers’ own volition.

Et luego [Pedro de Villanueva] mandó a todos los moros vesinos en el dicho logar de Çenet que allí estavan llegados en el logar acostumbrado de se llegar que los dichos moros e los susçeusores de aquellos al dicho señor maestre e orden de susodicha de aquí adelante ayan e tengan por señores suyos del dicho logar de // Çenet

(“And then he [Pedro de Villanueva]ordered all the Moorish neighbours from that village of Çenet, who were in the usual place, that they and their successors would have the Master and the aforesaid Order, or whomever they [the Order of Santiago and their representatives] may choose, as their lords and lords of that village of Çenet from that moment onwards”)

To this, the charter adds, also in the subjuctive mode, “and that they obey and follow the orders of said master and order” (respondan e satisffagan et los mandamientos del dicho señor maestre e orden).

The use of the verb mandar frames the actions to be carried out by Muslims, which are expressed in subjunctive mode subordinate to the main action. In this way, the grammar of these action phrases also subordinates the actions of the Muslims (ayan e tengan por señores suyos; respondan e satisffagan) to that of Pedro de Villanueva (mandó a los moros). The formulation of the action phrases and the way in which they relate to each other leave no doubt that the Muslim inhabitants were given to their new lords just like the houses and other possessions of the village, even if they performed the ceremony that made the homage legally binding themselves. The obedience the Muslims owed to their erstwhile lord Pedro de Villanueva determined their future deference to the Order of Santiago, even after the original bond had expired.

In order for such a transition to be legal, however, vassals needed to be free of their previous lord to accept their new one. For this reason, the text also states that

Pedro de Villanueva suelta e quita e llama (sic) los dichos moros e los bienes de aquellos de toda naturalesa de fialdat jura e omenaje en los quales el dicho don Pedro de Villanueva \en alguna cosa/ fuesen tenidos e obligados.

(“Pedro de Villanueva frees and exempts and delivers said Moors and their property from every form of fealty, oath, and homage to which they were obligated towards said Don Pedro de Villanueva.”)

In this action phrase as well, Pedro de Villanueva is the actor and the Muslim inhabitants of Çenet are the recipients. In this case, he releases them from his own lordship as a necessary step for the transition.

An expression indicating compulsion is repeated further down in the text, where it describes how all of the Muslims – here identified individually by their names – swore fealty to the representatives of the Order of Santiago:

avido speçial mandamiento del dicho don Pedro de Villanueva, fisieron jura de fialdat a los dichos procuradores en el logar del dicho señor maestre e orden de suso dicha, segund que es acostumbrado de faser, et prometieron a los dichos procuradores por ellos e les susçeu//sores suyos que de aquí adelante responderán al dicho señor maestre e a la dicha orden o a quien ellos querrán por todos tiempos assi como a verdadero e a natural señor suyo de todas e cada una rentas exidas esdivenimientos del dicho logar de Çenet.

(“having received special order from Don Pedro de Villanueva, they [the Muslims] swore fealty to the aforementioned Master and Order, as it is custom, and promised to the representatives, for themselves and their successors, that from now on they would answer to said Master and Order, or to whomever they [the Master and Order] may choose, for each and every income, yield, and activity or other rights of said village of Çenet.”)

This is the first action phrase that features the Muslims as active participants in the proceedings. It is conditioned, however, by an order from their Christian lord (avido speçial mandamiento, “having received special order”) as well as by an existing tradition (segund que es acostumbrado de faser, “as it is custom”). The action phrase is formulated in the indicative mode (fisieron jura de fialdat,“they swore fealty”; prometieron, “they promised”) and has the Muslims pledging fealty to their new lords, thus complying with the agreement reached between Pedro de Villanueva and the Order of Santiago.

The content and structure of the action phrases relating to Muslims up to this point situates them as passively transitioning from one submission to another, as indicated by the statement that they acted on speçial mandamiento or special orders of Pedro de Villanueva as well as by the fact that the action phrases feature the Muslims as objects or recipients or have them appearing as subjects only in subordinate clauses.

Now, however, the action phrases depict Muslims as active participants in the procedure of entering the new relationship of dependence. This is apparent in the fact that the verbs describing their actions are in now the indicative mood (fisieron jura de fialdat a los dichos procuradores ... et prometieron ... que de aquí adelante responderán al dicho señor Maestre,“they swore fealty to the representatives ... and promised ... that from now on they would answer to said Master”).

The subsequent action phrases serve to ensure that the Muslims would henceforth answer to and obey the master and order, as stated in the first clause. First, they offer their property as collateral (obligaron,“obligated”), once again expressed using a verb in the indicative mode to portray them as active participants in the proceedings that were recorded in writing.

Et por las dichas cosas tenederas e complideras obligaron al // dicho señor maestre e orden de suso dicha, ausentes, et a los sobredichos procuradores presentes en logar del dicho señor maestre e orden de suso dicha e a los sus sçepsores (sic) suyos todos los bienes suyos e de la dicha aljama do quier que sean avidos e por aver.

(“And to maintain and fulfil the aforesaid things, they obligated themselves and their possessions and those of the said aljama [= Muslim community], wherever they are or will be, to the aforementioned Master and Order, who are absent, and to the said representatives present in their stead as well as to their successors.”)

In this clause, the Muslims offer both their personal and communal goods as securities for the fulfilment of their obligations, as well as emphasizing the fact that they would obey their lords in every way. Given that, while determining the value of the property, the text later states that the village was “leased” (arrendar, “to lease”) to the Muslims in exchange for an annual payment, it is difficult to discern exactly what possessions they offered as security. Considering the size of the community and its rural profile, this most likely referred to their movable goods and livestock.

They subsequently reinforced their obligation by verbally expressing their loyalty to their new lords in the shape of an oath taken in their own language and related to their own religion.

Por tal que las dichas cosas por los dichos moros sean mejor complidas e guardadas juraron por el alquibla segund çuna de moros, es a saber: “vile aledi leyle alehu” todas las dichas cosas tener e complir e en alguna cosas non contra faser.

(“For the mentioned things to be better fulfilled by said Moors, they swore by the alqibla following their law”vile aledi leyle alehu” that they would fulfil all these things and would not go against any of them.”)

Finally, they carried out the gestural representation of the new bond following the feudal tradition predominant in Europe.

Et fisieron a los sobredichos procuradores en el dicho logar del dicho señor maestre e orden de suso dicha fe e omenaje de manos tan solamiente acomendado.

(“And they paid homage only with their hands to the representatives in said place for the mentioned Master and Order.”)

The homage ceremony performed by the Muslim inhabitants of Çenet was similar to that of their Christian counterparts (using words and the gesture of taking their hands). It was adapted to their cultural and religious particularities, however: Specifically, the text reflects that they pledged according to Muslim custom (Sunnah) while looking towards the qibla and using their own standard expressions (which the scribe transcribed phonetically). By having Muslims swear by their own law, religious difference was built into the transition of lordship. This adaptation did not detract from the efficacy of the homage, however – in fact, it might even be argued that it had the opposite effect. Allowing Muslims to swear according to their own tradition lent more potency to the gesture than forcing them to swear by another they did not believe in. In fact, during most of the Middle Ages, it was common practice to allow Muslims under Christian rule in the Iberian Peninsula to swear by the Qur’an.8

Following this formality, the representatives of the Order of Santiago commanded the Muslim inhabitants of Çenet to temporarily obey their previous lord for the duration of his life that of his heir after his own death, despite being under the lordship of the Order of Santiago:

Et luego los dichos Ferrand Ruys e Martín Yuanes procuradores susodichos con la presente carta mandaron a los sobredichos alamín e moros abitadores en el dicho logar que presentes eran que de aquí adelante respondan al dicho don Pedro de Villanueva por vida suya et después de sus días en la vida de un heredero suyo

(“And then said representatives Ferrand Ruys and Martin Yuanes ordered with this charter the aforementioned alamin [= leader of the Muslim community] and Moorish inhabitants of the village who were present to answer from this day onwards to Don Pedro de Villanueva during his life and, after his death, during the lifespan of one of his heirs”)

In this action phrase, Muslims are once again the recipients of a command issued by their new lords, as indicated by the use of the verb mandar followed by the actions the Muslims were to carry out in subjunctive mode (respondan, they answer). This mandate is followed by a repetition of the same formal gestures by the Muslims (offering their possessions as collateral, oath of fealty, and gesture of hands to signify the submission), this time they directed towards Pedro de Villanueva. The wording of these action phrases repeats the formulas used to describe their submission to the Order of Santiago.

The analysis of the structure of the text and its action phrases shows that Muslims played a secondary (although very necessary) role in the proceedings. The change of lordship over the settlement is the central subject of this charter as well as the two others pertaining to the other exchanged villages. The actions of the Muslims are a consequence of the principal action and derived from it. This is why the first part of the charter refers to and relates the original agreement, but also why the text does not deal with the practicalities and implications of the new dependence relationship or the mechanisms through which it was supposed to function on a day-to-day basis, as we will see.

It is also reflected in the roles assigned to Muslims in the actions expressed in the text. The formulation of the action phrases indicates that the actions taken by the Muslims were not carried out at their own initiative. The text repeatedly shows that their lords ordered them what to do when and where, for example through the frequent use of the verb mandar in the principal clauses preceding the descriptions of the Muslims’ actions: ... Et luego mandó a todos los moros vesinos ... [los moros] avido speçial mandamiento del dicho don Pedro de Villanueva ... mandaron a los sobredichos alamin e moros abitadores (“he then ordered all the Moorish neighbours” ... “[The Muslims]having received special order” ... “they ordered the aforementioned alamin and Moorish inhabitants”). Every action phrase involving the Muslim inhabitants as actors is preceded by an order or request.By contrast, however, no such expressions are used in the context of the actions of Pedro de Villanueva or the representatives of the Order of Santiago.

The Muslims always thus always at the instance of their lord, and even though they had been formally released from their previous bond, Pedro de Villanueva’s mandate remained in force. But despite their lack of agency stated explicitly in the wording of the charter, the acquiescence and collaboration of the Muslim inhabitants was still required to make the exchange effective and legitimate.

The final section of the charter states the value of the village, which was determined by way of the representatives of the Order of Santiago having both Muslim and Christian officials declare under oath how much revenue it produced. In this context, the charter includes the following passage:

quel dicho logar se arrendava cada un año a los dichos moros del dicho logar por dos mill e siete çientos e veynte sueldos de reales e más

(“the said village was leased each year to said Moors who lived there for over 2,720 sueldos de reales”)9

The use of the verb arrendar (“to lease”) in the description of the worth of the village – even if the revenue was produced by its inhabitants and collected from them – implies that the Muslims did not own the land and had to pay for the right to live there. Other charters lying down the terms of Muslim settlements likewise state (explicitly or implicitly) the payment of the due taxes as a necessary condition for the relation established between the respective Muslims and their Christian lords. However, the verb arrendar is not found in any other known cases.

Moreover, there is no detailed description of the obligations the Muslim inhabitants of Çenet had to fulfil. Only the minimum total revenue amount expected is declared in the text, according to the heads of the Muslim community and corroborated by Christian officials who had been administering the flow of income generated, both on the Muslim and on the Christian side. Nor is any information provided on how this sum was collected. In other charters codifying agreements between military orders and Muslims as settlers, the fiscal obligations are itemized and described with a certain level of detail, occasionally also including due dates by which they were to be settled. In the charter examined here, the obligations are merely mentioned as a lump sum. It is possible that this amount was the result of adding up the various taxes the Muslims owed to their lord, which would generally have included a percentage of their production, payments for seignorial rights such as the use of the oven, and taxes of Islamic origin that persisted in some way under Christian rule.

This lack of details can be attributed to different causes. For one, it might simply be because the change of lordship did not entail significant differences in the conditions of the Muslims’ dependence. Such continuity regarding the terms of obligations can also be found in other places where Muslim settlements were transferred from other Christian lordships to the rule of military orders. On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that the Order of Santiago issued a separate charter – now lost – to the Muslim community in which the terms of the new relationship were defined in greater detail.

Interpreting the text within its context

The events giving rise to the charters in this dataset took place in the southern part of the Kingdom of Valencia during the middle of the fourteenth century. The conquest of the Kingdom of Valencia by King Jaume I in the mid–13th century triggered a reorganization of the territory and its largely Muslim populations, which were reframed and integrated into feudal structures.10 The king delegated much of the administration of the territory to noblemen, military orders, and other lords who formed a new human and administrative landscape through the establishment of bonds of dependency with the inhabitants in their lands.

This was the basis for the events recounted in the studied charter. The Order of Santiago reached an agreement with another territorial lord to exchange several villages – along with their inhabitants – located in the southern part of the kingdom, with the apparent goal of consolidating the order’s possessions in the area and providing more safety for their inhabitants.11 The other lord was Pedro de Villanueva, a son of the Mayor Commander of the Order of Santiago in Aragon. Given the relationship between the parties and the fact that the agreement was concluded in the midst of a military campaign against the Nasri Kingdom of Granada (it was issued in the Castilian military camp during the siege of Alcalá la Real), it is quite possible that there was a secondary motivation not expressed in the document, although this cannot be confirmed.12 In any case, the exchange was apparently favourable for the order in the long term, as it obtained two villages that were larger and more secure than the one traded for them. However, the implementation of the agreement in the documents compensated Pedro de Villanueva by allowing him to enjoy lordship over the three villages during his lifetime and that of one of his descendants.

One of the protagonists of this story is the Order of Santiago, one of the military orders created on the Iberian Peninsula during the 12th century. These religious institutions became the armed branch of the Catholic Church and focused on defending not only various holy sites but also all of Christendom against its external enemies. The territorial expansion of the Christian kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula at the expense of the lands under Muslim rule presented excellent opportunities to justify their existence and prove their usefulness. It also created a fertile ground on which military orders could prosper. Orders originating from the Holy Land, such as the Hospitallers and the Templars, settled on Iberian lands and were soon joined by other military orders created in the different kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula: The Orders of Santiago, of Calatrava, of Alcantara, and of Avis were established in a first wave during the second half of the 12th century. The forceful dissolution of the Order of the Temple and the seizure of its possessions facilitated the creation of the Order of Montesa in the Crown of Aragon and the Order of Christ in Portugal at the beginning of the 14th century. These military orders built their image around their role as instruments for the fight against the enemies of Christendom – embodied by Islam and its different political and territorial manifestations. For this reason, and because of their defensive capabilities, they were granted properties in frontier areas and elsewhere throughout the Middle Ages, but especially in the aftermath of the territorial gains. In this way, military orders often became owners and administrators of large swaths of land. They were not only in charge of defending them, but also of making them profitable in order to secure their own upkeep and that of their war efforts.

The Order of Santiago had its most extensive possessions in the Kingdoms of Portugal (mostly in the areas of Alentejo and the Algarve) and Castile (in the area south of the river Tagus and north of the Sierra Morena, as well as in the Kingdom of Murcia). To a lesser extent, it also held lands in the Crown of Aragon, especially in the Kingdom of Valencia and the present-day province of Teruel. The order’s territorial holdings in the Valencian kingdom, where the villages of Çenet, Sagra, and Agna were located, consisted mainly of non-contiguous patches.

In these areas, like in many other places, there were Muslim inhabitants on the land before the military order took over. The origin of these populations is not always clear; in the context of the Kingdom of Valencia, they seem for the most part to have been living there under Islamic rule, and they remained on the land after the Christian conquest. Whether previously already on the land or brought in purposely to live and work on it, Muslim populations were sometimes instrumental in making lands profitable for the military orders.

The mechanisms used by military orders to incorporate Muslims into their lordship and the relationships of dependence they forged with them were not homogeneous. Muslim settlers could formalize their relations with the orders by way of written agreements or through charters granted unilaterally by their new lords. It was also common for no charter to be drafted at all, with the terms of the new relationship only established verbally and never put into writing.13

The resulting relationships of asymmetrical dependence were not dissimilar to those established between Christian settlers and their lords elsewhere in western and central Europe, so it is easy to draw parallels between them. In some cases, Muslims experienced severe restrictions regarding their agency and were attached to the land, while at other times they retained more rights and some degree of freedom. Nevertheless, religious difference was an important and unavoidable component built into the relationships of dominion between Muslims and military orders. This means that even though similar mechanisms were used within the Christian kingdoms to incorporate Muslim settlers into the frameworks of dependence (as vassals, serfs, or in other forms), the status and conditions they experienced were never equal to those of Christians. They kept their own law and often their forms of government separate from those of Christians (even if their autonomy degraded over time), and they were usually at a disadvantage compared to their Christian neighbours in terms of social and economic progress, among other aspects.

The ways and mechanisms that made the presence of Muslim settlers profitable for their lords were largely defined upon their entrance into a lordship. On some occasions, Muslims came to agreements with their new lords, while on others they were forced to accept certain conditions without any say. Sometimes, major questions regarding the establishment of such relationships remain unanswered, and written documents such as the ones included in this dataset can often shed a revealing light on this issue.

Muslims inhabited the three settlements involved in the exchange studied here. However, the initial agreement reached between Pedro de Villanueva and the representatives of the Order of Santiago issued on 14 July 1341only refers to the inhabitants generically without specifying their religion:

con todos los omes e mujeres de qualquier condiçion que sean, que agora y moren o moraren de aqui adelante

(“with all of the men and women of whichever status that live there now or will live there in the future”)14

The analysed charter mirrors the fact that the inhabitants of the settlement of Çenet – that is to say, the people who actually performed work and produced profit for their lords – were only secondary actors in the actions described in the dataset. This is manifest both in the text structure and in the way the residents’ actions are portrayed in it.

Because of the particular aspect of the exchange that granted continued power over the village to Pedro de Villanueva and his heir, the Muslim inhabitants of Çenet had to perform two separate ceremonies of swearing fealty: once to the representatives of the order, their new lords, and then once more to their former lord Pedro de Villanueva, who would continue to act as such. The description of the proceedings is identical in both cases.

The role of the Muslims’ actions within this procedure was to seal and make the agreement among the Christian lords effective. Securing the compliance of the inhabitants was important in arrangements such as this one, and even if they were forced to do so, the formal submission of the people living in of Çenet was required to legitimize and recognize the new lordship and allow the Order of Santiago to benefit from their work.

The Muslims of Çenet had no agency in the decision-making progress leading to their change of lordship. This is reflected in the structure and formulation of the charter: Despite being described as having possessions both individually and as a collective, it is implicit that they ultimately did not enjoy full proprietary rights over the place they lived in and the lands they worked. Their permanence there was strictly subject to the fulfilment of their annual fiscal obligations towards the lords who owned the settlement. This greatly limited the freedom of the Muslims inhabiting the village – an interpretation further supported by the passive role they play in the action phrases. Despite actively accepting their new lords, they are portrayed as receivers of the effects of the actions taken by their Christian lords.

It is difficult to ascertain how widespread this state of vulnerability was among Muslims under the lordship of military orders or others. It should be noted that the levels of coercion experienced by the specific Muslim settlers studied here appear in relatively stark contrast to the situation of other Muslim communities under the rule of military orders in the Kingdom of Valencia.15 Only further and more extensive analysis of written records relating to the entry of Muslims into relationships with military orders or other lords can lead to a better understanding of the bonds of dominion that were established, along with the common and diverse obligations and rights they implied.

Footnotes

This article was developed within the framework of the research project “Between Coexistence and Dominance: Muslims under the Rule of Military Orders in the Iberian Peninsula” funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Projektnummer 337290382) and finalized as part of the research project “Musulmanes en tierras de señorío: una visión integrada” funded by the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (2020 T1/HUM-20291).↩︎

This approach is inspired by Maria Ågren, Making a Living, Making a Difference: Gender and Work in Early Modern European Society, Oxford 2016.↩︎

Juliane Schiel, Johan Lund Heinsen, and Claude Chevaleyre, “Grammars of Coercion: Towards a Cross-Corpora Annotation Model”. Working paper related to the working group “Grammars of Coercion” of the Cost Action “Worlds of Related Coercions in Work”. Available online: https://dkan.worck.digital-history.uni-bielefeld.de/sites/default/files/working-paper/Working%20Group%20Paper_WG%201.pdf (5 June 2023).↩︎

17 July 1341. Alcalá la Real. Archivo Histórico Nacional (Madrid), Órdenes Militares, folder 307, document 7.↩︎

The documents of this dataset can be found at https://dkan.worck.digital-history.uni-bielefeld.de/?q=dataset/transferring-land-and-people-muslims-%C3%A7enet-sagra-and-agna-and-order-santiago-1341 (5 June 2023).↩︎

A transcription of this document has been published by Manuel López Fernández, “El Maestrazgo de Alfonso Méndez de Guzmán en la Orden de Santiago (1338–1342)”, Historia, Instituciones, Documentos, 44 (2017), pp. 151–178. It has been included in the dataset for the sake of completeness.↩︎

The documents are preserved at Archivo Histórico Nacional (Madrid), Órdenes Militares, folder 307, documents 6, 7, and 8.↩︎

Federico Corriente, “A vueltas con las frases árabes y algunas hebreas incrustadas en las literaturas medievales hispánicas”, Revista de Filología Española,LXXXVI, 1ª (2006), pp. 105–125. I am grateful to Prof. Cristina de la Puente for her assistance in identifying this formula and its use.↩︎

This is not necessarily a large sum considering that the lease for a textile mill in the 14th century could be as high as 1,000 sueldos (Juan Vicente García Marsilla, “Los colores del textil. Los tintes y el teñido de los paños en la Valencia medieval”, in L’Histoire à la source: acter, compter, enregistrer (Catalogne, Savoie, Italie, XIIe-XVe siècle) : Mélanges offerts à Christian Guilleré.Université Savoie Montblanc, 2017, vol. 1, pp. 283–315, here p. 305.↩︎

Robert Ignatius Burns, The Crusader Kingdom of Valencia: Reconstruction on a Thirteenth-Century Frontier. Harvard University Press, 1967.↩︎

The motivation as established in the original agreement reads as follows: “E porque nos, la dicha nuestra orden avemos en el lugar de Anna, que es asentado en el regno de Valençia en frontera de Castilla, en el qual lugar fasen muy gran daño almogavares e otras malas gentes e entendiendo, otrosí, que en los dichos lugares de Sagra e Çenet ay más vasallos e pobladores que en el dicho lugar de Anna, por esta rasón e por otras que a nos e a nuestra orden mueve.” (“And because we, the said order, have the village of Anna in the Kingdom of Valencia at the border with Castile, where almogavares [frontiersmen and foot soldiers in frontier areas] and other bad people do great damage, and also considering that the villages of Sagra and Çenet have more vassals and inhabitants than the village of Anna, for this reason and for other reasons that lead us to act [this way]”). Fernández, “El Maestrazgo de Alfonso Méndez de Guzmán”, here pp. 174–175.↩︎

The Order of Santiago is known to have been compensated for their services in the form of favourable purchases of castles and landed estates at the beginning of the 14th century. In those cases, the text itself does not express this secondary goal explicitly. See Clara Almagro Vidal, “More than Meets the Eye: Readings of Economic Interactions between Religious Minorities in Medieval Castile”, in Clara Almagro Vidal, Jessica Tearney-Pearce, and Luke Yarbrough (eds.), Minorities in Contact in the Medieval Mediterranean, Brepols, 2020, pp. 233–245.↩︎

Clara Almagro Vidal, “Musulmanes como (re)pobladores en tierras de las órdenes militares: Primeras observaciones”, in Isabel Cristina F. Fernandes (ed.), Ordens militares, identidade e mudança, vol. 1, pp. 231–246, here pp. 242–243.↩︎

Archivo Histórico Nacional, Sección de Sellos, folder 101, document 2. Publ. Fernández, “El Maestrazgo de Alfonso Méndez de Guzmán”, p. 175.↩︎

Clara Almagro Vidal, “Grammars of Dependence: A Historical Semantics Approach to Population Charters Granted by Military Orders to Muslims in Medieval Iberia”, Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften, 24 (2023), forthcoming.↩︎